© 2018 iStock/Kondoros Eva Katalin

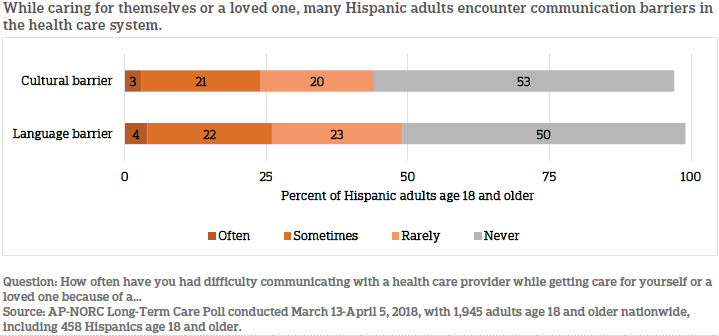

More than half of Hispanic adults have encountered a communication barrier in the health care system, and they turn to a variety of formal and informal sources for help in overcoming these obstacles, according to a new study conducted by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. The study finds that half of these Hispanic adults age 18 and older rely on family or another health care provider to help resolve language or cultural difficulties in the health care system, while more than a quarter have relied on a translator, public resources in their community, or online sources for assistance.

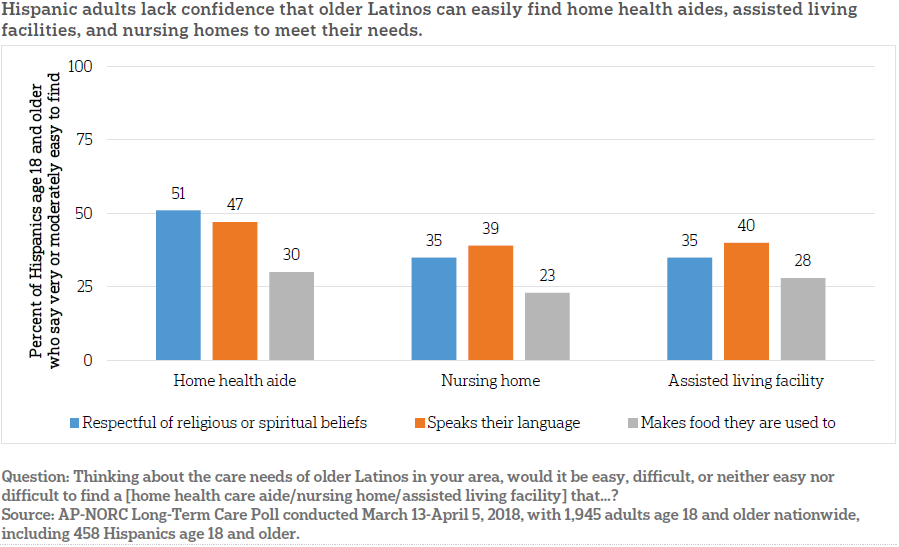

Along with these communication difficulties, the survey also finds that many Hispanics are concerned about the cultural accommodations long-term care services in their area may or may not make. Asked about older Latinos in their area, less than half say it would be easy for them to find nursing homes, assisted living facilities, and home health aides that speak their language, while less than 3 in 10 say the same about providing the kinds of food they are used to. Some are also concerned about the availability of long-term care services, particularly nursing homes and assisted living facilities, that will respect their religious or spiritual beliefs.

The number of Americans age 65 and older is expected to nearly double by 2060,1 and nearly 7 in 10 older Americans need long-term care at some point in their life.2 Projected forward, this increasing demand for long-term care services will put a strain on the individuals, families, and government programs that support this care. The proportion of Hispanics among those age 65 and older is expected to grow in the coming years,3 making their attitudes and expectations for care a critical area of study.

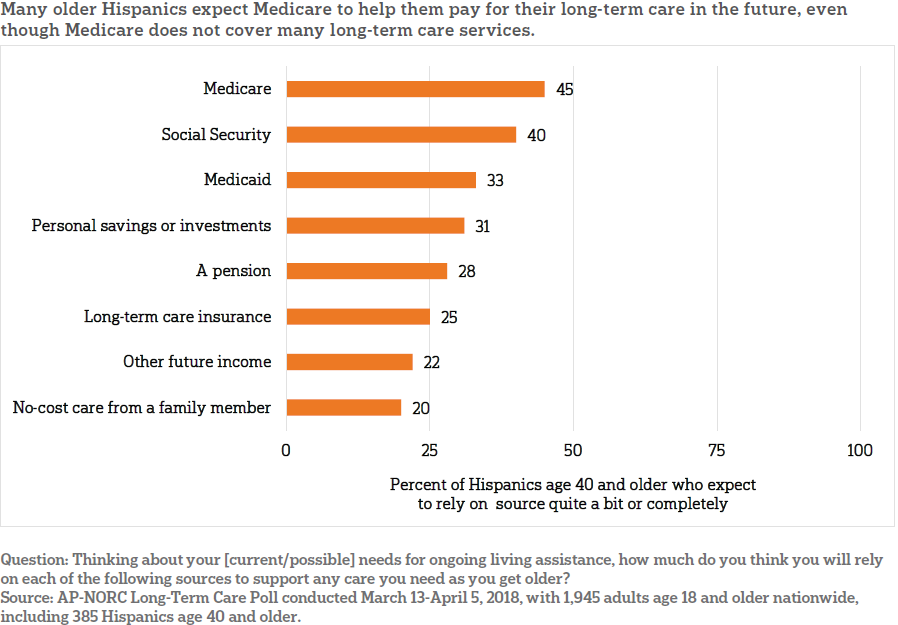

Like older Americans overall, many Hispanics age 40 and older expect to rely on government programs like Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid to pay for care they may need as they grow older. But, only about 2 in 10 expect these programs to provide at least the same level of benefits five years from now as they do today. And overall, just 15 percent of Hispanics age 40 and older feel confident they will be able to pay for the care they might need in the future.

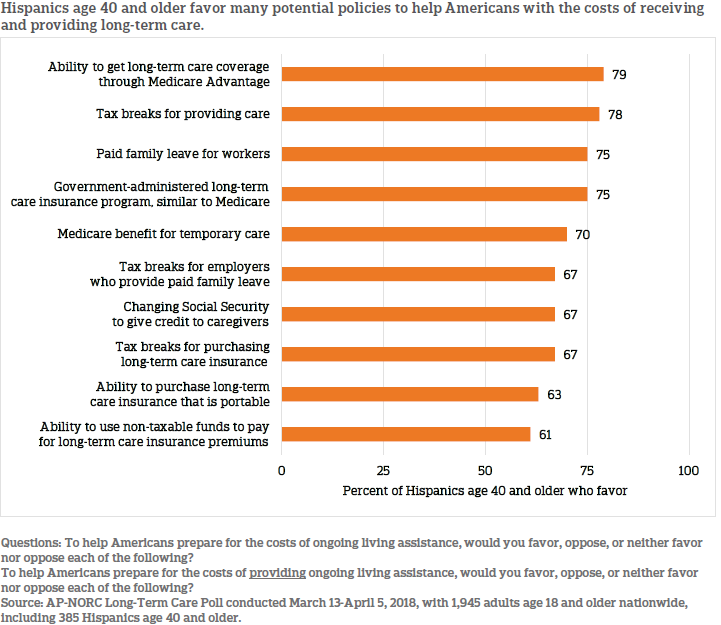

While older Hispanics lack confidence in the stability of current government programs and their own financial preparedness, support for new proposals like the ability to get long-term care coverage through Medicare Advantage, tax breaks for those who provide care, paid family leave, and a government-administered long-term care insurance program is high.

The survey also finds an openness to the use of telemedicine for services like medical consultations, managing chronic conditions, and urgent health concerns. More than 6 in 10 older Hispanics say they would be comfortable receiving care via the telephone, live video services like Skype, or text messages for each of these reasons for seeking care.

The AP-NORC Center conducted this study with funding from The SCAN Foundation. The nationwide poll was conducted March 13 to April 5, 2018, and consists of 1,945 interviews with a nationally representative sample of Americans using the AmeriSpeak® Panel. It includes interviews with 458 Hispanic adults, including 385 Hispanics age 40 and older.

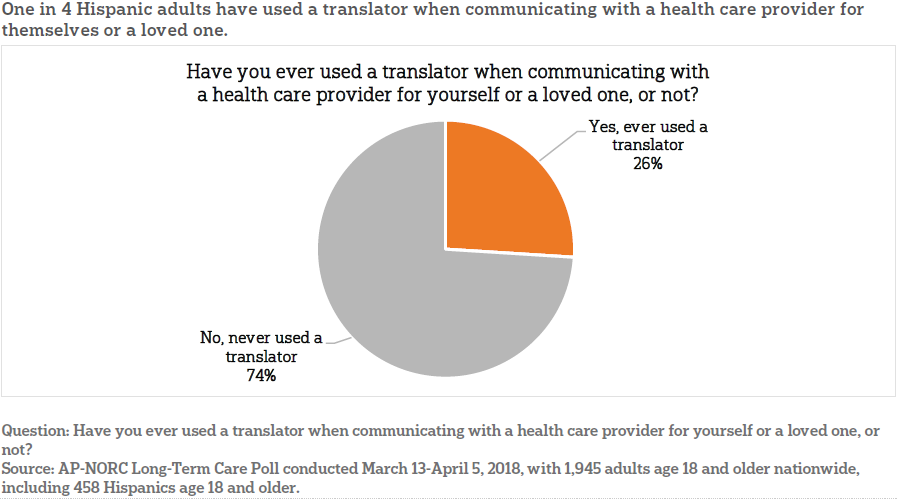

Additional findings from this study include:

- Many Hispanics are concerned about the cultural accommodations of long-term care services available to Latinos in their area. Less than half say it would be easy to find a home health care aide, nursing home, or assisted living facility that speaks their language. Fewer say it would be easy to find long-term care services that can make the food they are used to.

- Eight-one percent of Hispanics age 40 and older would be comfortable with some form of telemedicine.

- While comfort with telemedicine is generally high among older Hispanics, they are less comfortable than non-Hispanics with some telemedicine services. For example, 52 percent of Hispanics age 40 and older are comfortable using the phone for medical consultation with their provider, compared to 68 percent of non-Hispanics age 40 and older.

- Four in 10 older Hispanics have experience providing care, and 65 percent do so for 10 or more hours per week, unpaid. Most say it’s stressful—28 percent report high stress from caregiving, and another 40 percent report moderate stress.

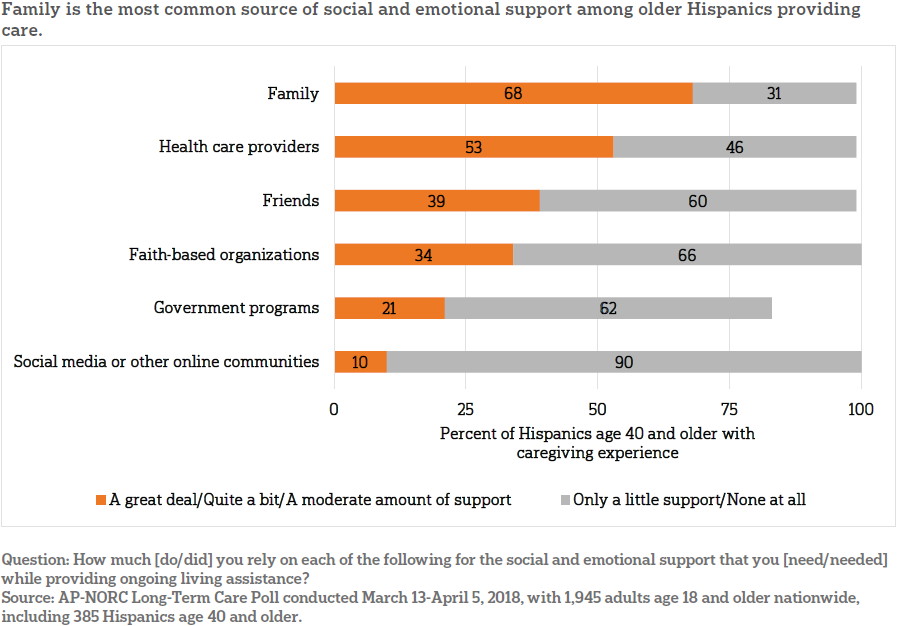

- Even though many are stressed, 46 percent of older Hispanics say they have all or most of the emotional and social support they need to provide care. The most common sources of support are family (68 percent), followed by health care providers (53 percent).

- Eighty-three percent of older Hispanics support employer-offered long-term care insurance plans. Of those, 48 percent prefer an opt-in program, and 48 percent prefer automatic enrollment.

- More than three-quarters of older Hispanics support policies like the ability to get long-term care coverage through Medicare Advantage or other supplemental insurance, tax breaks for those who provide care, paid family leave, and a government-administered long-term care insurance program.

Additional information, including the survey’s complete topline findings, can be found on The AP-NORC Center’s long-term care project website at www.longtermcarepoll.org.

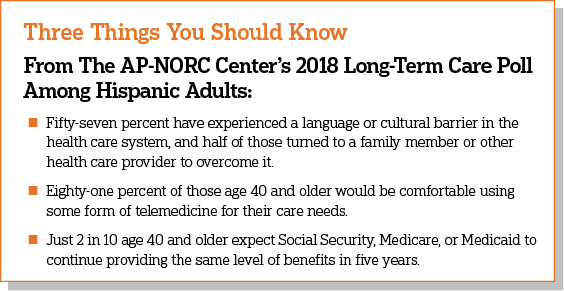

MORE THAN HALF OF HISPANICS HAVE FACED A COMMUNICATION DIFFICULTY WITH A HEALTH CARE PROVIDER.ꜛ

For a majority of Hispanics, navigating the health care system has an added layer of difficulty. Overall, 57 percent of Hispanic adults report experiencing difficulty communicating with a health care provider due to either a language or cultural barrier while getting care for themselves or a loved one. Those who were born outside the United States are more likely than others to experience communication challenges due to a language barrier (65 percent vs. 40 percent).

When it comes to overcoming these communication challenges, Hispanic adults draw on a variety of resources for help. Half who have experienced a language or cultural barrier sought out other family members or another health care provider for assistance. About a quarter sought help from a translator, public community services, or online sources. About 2 in 10 looked for materials on the Medicare or Medicaid website. Fewer turned to social media or charity or religious groups.

A majority (59 percent) of Hispanic adults who have experienced a communication barrier with a health care provider sought help from multiple resources, while 22 percent sought assistance from just one source. However, some do not seek any help at all—19 percent say they did not seek out doctors, family, translators, community services, or other sources for help when they experienced these communication difficulties.

Among Hispanics who experienced a language or cultural barrier, those who completed the survey in Spanish were more likely to seek help and to look for it from multiple sources. Virtually all (96 percent) Spanish language survey-takers who experienced a barrier sought at least one source of help, with an average of four sources sought, compared to 77 percent, with an average of two sources sought, for Hispanics who completed the survey in English.

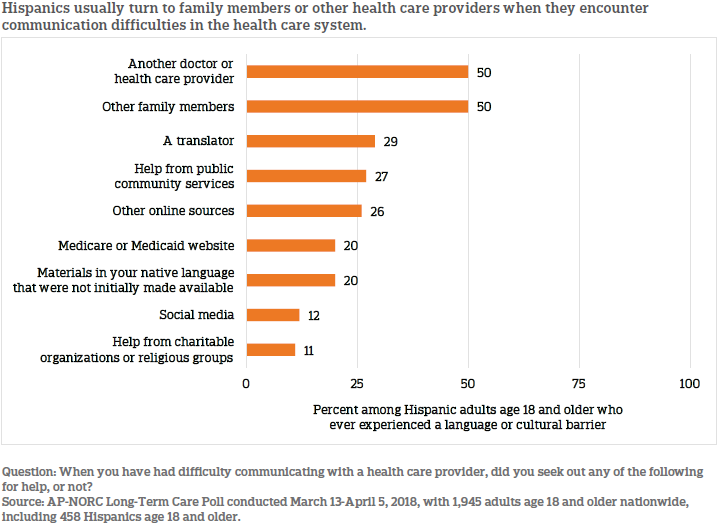

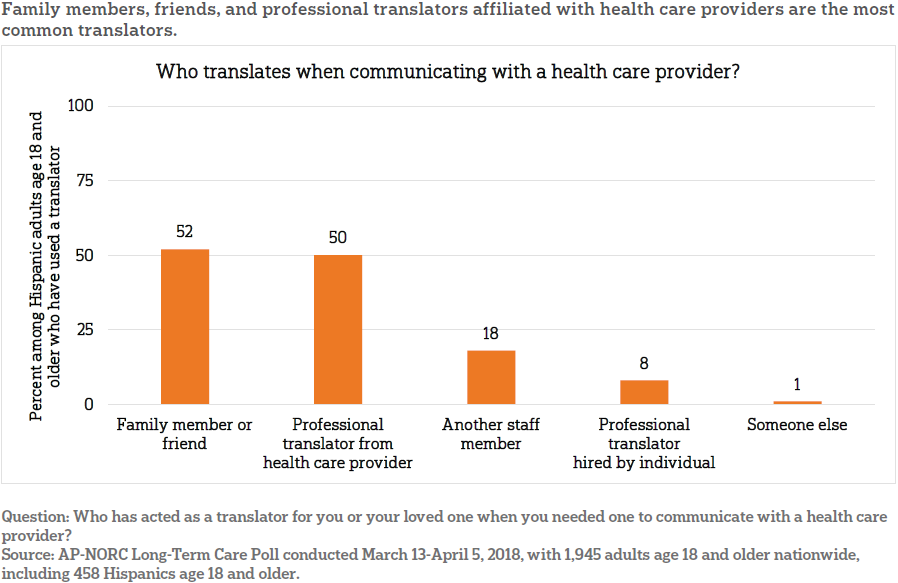

A QUARTER OF HISPANICS HAVE USED A TRANSLATOR WHEN COMMUNICATING WITH A HEALTH CARE PROVIDER.ꜛ

Twenty-six percent of Hispanics have used a translator—either a formal or informal one—when communicating with a health care provider, and among those who completed the survey in Spanish and those born outside the United States, the use of a translator is more common, with over half of these groups using one.

Both informal and professional translators are commonly used to translate communications with health care providers. About half of Hispanics needing a translator turned to a family member or friend, and a similar number used a professional translator who worked with the health care provider. Fewer used another staff member at the health care provider or a professional translator they hired themselves.

For those Hispanics who see health care providers that receive funding from Medicare or Medicaid, free translation services may be an option. Although the government has conducted outreach with limited English proficiency individuals to increase awareness of these services,4 most Hispanic adults (68 percent) are unaware of the availability of free translators through Medicare or Medicaid. Hispanics who experienced communication difficulties due to a language barrier, completed the survey in Spanish, are Medicare or Medicaid beneficiaries, or were born outside the United States are no more likely than others to be aware of these free translation services.

MANY HISPANICS DOUBT THE CULTURAL COMPETENCE OF LONG-TERM CARE SERVICES IN THEIR LOCAL AREA.ꜛ

In 2017, The AP-NORC Center found that many Hispanics age 40 and older held doubts that the long-term care services in their local area would be able to meet the cultural needs of older Latinos. Only about 2 in 10 said they were confident that home health aides, nursing homes, or assisted living facilities would be able to accommodate their cultural needs.5

This year’s survey explored the specific cultural accommodations older Latinos may require, including their language, food, and spiritual preferences, and asked how easy or difficult they thought it would be to find long-term care services in their area that can meet those needs. It finds that confidence in home health aides is highest compared to nursing homes and assisted living facilities. But, older Hispanics are skeptical in the ability of any of these services to offer the kinds of food older Latinos are used to.

About half of Hispanics say they could easily find a home health aide for older Latinos in their local area who speaks their language and is respectful of their religious beliefs. But, just 30 percent say the same about providing the kind of food they are used to.

For nursing homes, just 39 percent say it would be easy to find one locally with staff who speak their language, and just 35 percent say it would be easy to find one with staff who respect their religious beliefs. Even fewer (23 percent) say the same about finding a nursing home that can accommodate their food preferences.

Similarly, few say it would be easy to find a local assisted living facility with staff who speak their language (40 percent), or who are respectful of religious beliefs (35 percent), or that provides the food they are used to (28 percent).

MANY OLDER HISPANICS ARE OPEN TO TELEMEDICINE SERVICES.ꜛ

Telemedicine, also referred to as telehealth, is a growing method for the delivery of health care. Using some form of telecommunications technology, such as the internet or a phone, telemedicine allows patients to receive health care services remotely.6 While not all health care providers offer telemedicine services, they can help make health care accessible to people who live far from medical services or to those with limited mobility or transportation options.

Earlier this year, Congress passed the CHRONIC Care Act, which expands telemedicine options for Medicare beneficiaries by allowing Medicare Advantage plans to cover additional telemedicine services, giving dialysis patients the ability to do monthly check-ins via telemedicine, and expanding diagnosis and treatment via telemedicine for stroke patients.7,8

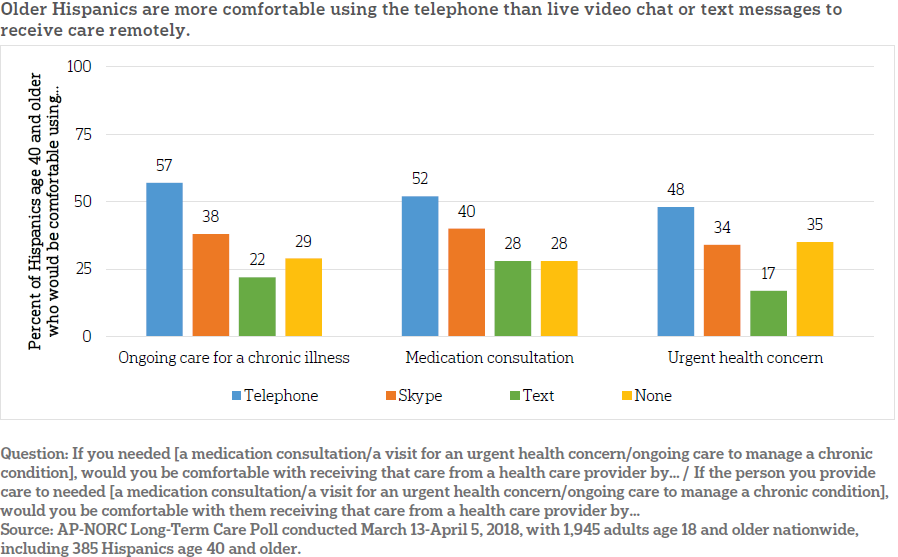

As access to telemedicine grows, this survey finds that support for telemedicine is high among Hispanics age 40 and older. Eighty-one percent are comfortable with the idea of using at least one form of telemedicine services, either for themselves or for an older loved one they provide care to, for a medical consultation, ongoing care to manage a chronic illness, or a visit for an urgent health concern.

Among older Hispanics, 7 in 10 would be comfortable using a form of telemedicine for a medication consultation or to manage a chronic condition. Fewer, but still more than 6 in 10, are comfortable using a form of telemedicine for an urgent health concern.

While Medicare typically only covers live audio-video communication, less than half of older Hispanics feel comfortable receiving medical care via a live video service like Skype.9 They are more comfortable talking on the phone for a medication consultation, for ongoing care to manage a chronic condition, or for an urgent health concern. Few are comfortable with the idea of receiving care via text messages, and 19 percent would not be comfortable using any of the forms of telemedicine asked about in the survey.

Older Hispanics are less comfortable with certain forms of telemedicine compared to non-Hispanics age 40 and older. While 68 percent of older non-Hispanics are comfortable with talking on the phone for a medication consultation, just 52 percent of older Hispanics are comfortable doing so. Similarly, older Hispanics are less comfortable than older non-Hispanics with using a live video service like Skype (38 percent vs. 58 percent) or text messages (22 percent vs. 35 percent) for ongoing care to manage a chronic condition.

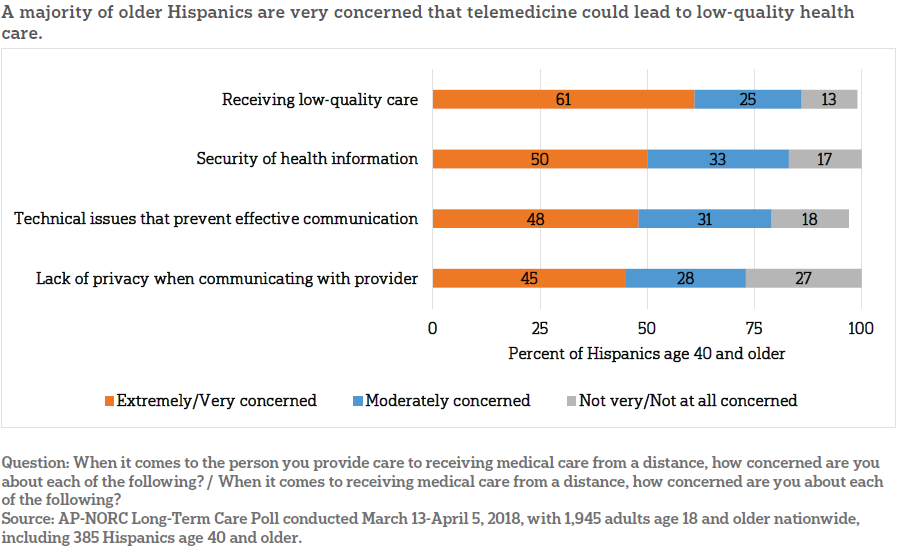

Older Hispanics have concerns about telemedicine, including receiving low-quality care, the security of their health information, running into technical issues that prevent them from communicating effectively, and lack of privacy when communicating with providers. And while many Hispanics and non-Hispanics express these concerns, older Hispanics are more likely than older non-Hispanics to be very concerned about a lack of security when it comes to telemedicine (50 percent vs. 38 percent).

HISPANICS PROVIDING CARE ARE STRESSED, BUT THEY FEEL SUPPORTED BY FAMILY AND HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS.ꜛ

Among the 4 in 10 Hispanics age 40 and older with experience as a caregiver, 65 percent say they spend 10 or more hours per week providing unpaid care, 22 percent say they spend between five and 10 hours a week providing care, and 12 percent spend five hours or less.

For many, the caregiving role brings stress and sacrifices. Seven in 10 feel either moderately (40 percent) or very/extremely (28 percent) stressed. Six in 10 feel they had to make sacrifices in their life to provide care, as well. Among those who had to give something up to provide care, free time (30 percent), the ability to leave the house or travel (16 percent), and their career, work, or education (15 percent) are the most common.

About half of these caregivers feel supported. Forty-six percent of older Hispanics with caregiving experience say they feel they have most or all of the social and emotional support they need to provide care. But, 32 percent say they only have some, and 22 percent say they have hardly any or none of the support they need. Older Hispanics providing care most often turn to family for support.

OLDER HISPANICS LACK CONFIDENCE THAT FEDERAL ASSISTANCE PROGRAMS WILL CONTINUE TO PROVIDE THE SAME BENEFITS.ꜛ

When thinking about how they might pay for long-term care expenses when they get older, Hispanics age 40 and older cite Medicare, Social Security, and Medicaid most often as sources they expect to rely on heavily to cover the costs of care. Personal savings and pensions are also commonly cited. Hispanics age 40 and older are less likely than non-Hispanics age 40 and older to say they will rely quite a bit or completely on Social Security (40 percent vs. 53 percent).

Even though at least a third of older Hispanics expect to rely on government programs like Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, few express confidence that these programs will continue to provide at least the same level of benefits in five years as they do now. Just 20 percent say they are very or extremely confident Social Security will still provide the same benefit in five years, even though it is adjusted for inflation. Similarly, 20 percent are confident Medicare will provide the same benefit, and just 16 percent believe that Medicaid will.

Even at their current benefit level these government programs may prove inadequate for many in covering the costs of care. In 2017, the average yearly income through Social Security for retirees was about $17,000.10 But, a part-time home health aide costs an average of about $49,000 annually in the United States, and a semi-private room in a nursing home costs about $86,000.11 Medicare rarely covers these types of expenses at all.

OLDER HISPANICS SUPPORT LONG-TERM CARE INSURANCE OFFERED THROUGH EMPLOYERS AND OTHER POLICIES TO HELP PAY FOR CARE.ꜛ

Long-term care insurance is one means available to help older Americans plan for the costs of long-term care. Among Hispanics age 40 and older, 11 percent say they have long-term care insurance currently, and about a quarter say they expect to pay for future care using long-term care insurance. But, a large majority supports employers offering long-term care insurance as a benefit, similar to how employers offer health, dental, or vision insurance. Overall, 83 percent support employers offering long-term care insurance as a benefit, including 40 percent who favor automatic enrollment in such a program and 39 percent who prefer it as an opt-in benefit. Just 13 percent oppose any employer-offered long-term care insurance.

Among government policies that have been suggested for helping Americans prepare for the costs of receiving and providing care, many enjoy majority support among older Hispanics. The ability to get long-term care coverage through Medicare Advantage or other supplemental insurance, tax breaks for those who provide care, paid family leave, and a government-administered long-term care insurance program are particularly popular.

ABOUT THE STUDYꜛ

Study Methodology

This study, funded by The SCAN Foundation, was conducted by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. Data were collected using AmeriSpeak®, NORC’s probability-based panel designed to be representative of the U.S. household population. During the initial recruitment phase of the panel, randomly selected U.S. households were sampled with a known, non-zero probability of selection from the NORC National Sample Frame and then contacted by U.S. mail, email, telephone, and field interviewers (face-to-face). The panel provides sample coverage of approximately 97 percent of the U.S. household population. Those excluded from the sample include people with P.O. Box only addresses, some addresses not listed in the USPS Delivery Sequence File, and some newly constructed dwellings. Of note for this study, the panel may exclude recipients of long-term care who live in some institutional types of settings, such as skilled nursing facilities or nursing homes, depending on how addresses are listed for the facility. Staff from NORC at the University of Chicago, The Associated Press, and The SCAN Foundation collaborated on all aspects of the study.

Interviews for this survey were conducted between March 13 and April 5, 2018, with adults age 18 and older representing the 50 states and the District of Columbia. Panel members were randomly drawn from AmeriSpeak, and 1,945 completed the survey—1,588 via the web and 357 via telephone. For purposes of analysis, adults age 40 and older and Hispanic older adults were sampled at a higher rate than their proportion of the population, then weighted back to their proper proportion in the survey, according to the most recent Census. Interviews were conducted in both English and Spanish, depending on respondent preference. Respondents were offered a small monetary incentive ($3) for completing the survey.

The final stage completion rate is 30.0 percent, the weighted household panel response rate is 33.7 percent, and the weighted household panel retention rate is 88.1 percent, for a cumulative AAPOR response rate 3 of 8.9 percent. The overall margin of sampling error is +/- 3.3 percentage points at the 95 percent confidence level, including the design effect. The margin of sampling error for the 1,522 completed interviews with adults age 40 and older is +/- 3.3 percentage points at the 95 percent confidence level, including the design effect. The margin of sampling error for the 458 completed interviews with Hispanic adults age 18 and older is +/- 9.5 percentage points at the 95 percent confidence level, including the design effect. The margin of sampling error for the 423 completed interviews with adults age 18 to 39 is +/- 6.7 percentage points at the 95 percent confidence level, including the design effect.

Once the sample has been selected and fielded, and all the study data have been collected and made final, a poststratification process is used to adjust for any survey nonresponse as well as any non-coverage or under- and oversampling resulting from the study specific sample design. Poststratification variables included age, gender, census division, race/ethnicity, and education. Weighting variables were obtained from the 2017 Current Population Survey. The weighted data reflect the U.S. population of adults age 18 and over.

All analyses were conducted using STATA (version 14), which allows for adjustment of standard errors for complex sample designs. All differences reported between subgroups of the U.S. population are at the 95 percent level of statistical significance, meaning that there is only a 5 percent (or less) probability that the observed differences could be attributed to chance variation in sampling. Additionally, bivariate differences between subgroups are only reported when they also remain robust in a multivariate model controlling for other demographic, political, and socioeconomic covariates.

A comprehensive listing of all study questions, complete with tabulations of top-level results for each question, is available on The AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research long-term care website: www.longtermcarepoll.org. For more information, visit www.apnorc.org or email info@apnorc.org.

Contributing Researchers

From NORC at the University of Chicago

Dan Malato

Jennifer Titus

Jennifer Benz

Liz Kantor

Trevor Tompson

From The Associated Press

Emily Swanson

About The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research

The AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research taps into the power of social science research and the highest-quality journalism to bring key information to people across the nation and throughout the world.

- The Associated Press (AP) is the world’s essential news organization, bringing fast, unbiased news to all media platforms and formats.

- NORC at the University of Chicago is one of the oldest and most respected, independent research institutions in the world.

The two organizations have established The AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research to conduct, analyze, and distribute social science research in the public interest on newsworthy topics, and to use the power of journalism to tell the stories that research reveals.

The founding principles of The AP-NORC Center include a mandate to carefully preserve and protect the scientific integrity and objectivity of NORC and the journalistic independence of AP. All work conducted by the Center conforms to the highest levels of scientific integrity to prevent any real or perceived bias in the research. All of the work of the Center is subject to review by its advisory committee to help ensure it meets these standards. The Center will publicize the results of all studies and make all datasets and study documentation available to scholars and the public.

Footnotesꜛ

1. Vespa, J., D.M. Armstrong, and L. Medina. 2018. Demographic turning points for the United States: Population projections for 2020 to 2060. Current Population Reports, P25-1144. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2018/demo/P25_1144.pdfꜛ

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2017. How Much Care Will You Need? https://longtermcare.acl.gov/the-basics/how-much-care-will-you-need.htmlꜛ

3. U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce. 2015. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdfꜛ

4. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2014. Strategic Language Access Plan to Improve Access to CMS Federally Conducted Activities by Persons with Limited English Proficiency. https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/OEOCRInfo/Downloads/StrategicLanguageAccessPlan.pdfꜛ

5. The AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. 2017. Long-Term Care in America: Hispanics’ Cultural Concerns and Difficulties with Care. https://www.longtermcarepoll.org/project/long-term-care-in-america-hispanics-cultural-concerns-and-difficulties-with-care/ꜛ

6. American Telemedicine Association. 2018. About Telemedicine. http://www.americantelemed.org/main/about/telehealth-faqs-ꜛ

7. Senate Finance Committee. 2017. CHRONIC Care Legislation Improves Care for Medicare Beneficiaries. https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/CHRONIC%20Care%20Act%20of%202017%20One-Pager%204.6.17.pdfꜛ

8. Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, Pub. L.115- 123. 2018. https://www.congress.gov/115/bills/hr1892/BILLS-115hr1892enr.pdfꜛ

9. Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2017. Telehealth Services. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/TelehealthSrvcsfctsht.pdfꜛ

10. Social Security Administration. 2018. Fact Sheet: Social Security. https://www.ssa.gov/news/press/factsheets/basicfact-alt.pdfꜛ

11. Genworth Financial. 2017. Genworth 2017 Cost of Care Survey. https://www.genworth.com/about-us/industry-expertise/cost-of-care.htmlꜛ