©2016 iStock/asiseeit

Many older Hispanics in the United States say they have faced language or cultural barriers as they navigate the health care system, with many experiencing serious setbacks because of it, according to a new study by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. Few say they have confidence that local nursing homes and assisted living communities will be able to accommodate their cultural needs.

The population of Americans age 65 and older is expected to grow rapidly in the coming decades, with the majority of these seniors likely to require at least some support with daily activities.1,2,3 The Hispanic population in particular is expected to make up an increasing proportion of those age 65 and older in the coming years.4

To continue its study into the long-term care experiences of American families, The AP-NORC Center conducted its fifth-annual Long-Term Care Poll in 2017. This study, which includes an oversample of older Hispanics, explores attitudes about ongoing living assistance and expectations and experiences with the health care system.

Hispanics may face additional obstacles in getting culturally competent care that other Americans may not. This study reveals that 49 percent of older Hispanics have already faced language or cultural barriers as they navigate the health care system. These barriers have resulted in additional stress, delays in getting care, increased time and effort, not getting needed care, and higher than expected costs for care. And while most who have either provided, received, or paid for long-term care describe feeling respected and valued throughout their experience, some express feelings of frustration, loneliness, and confusion.

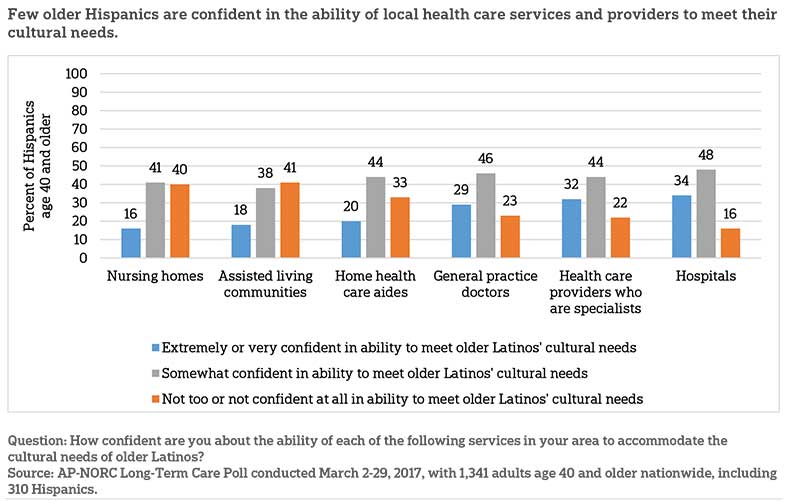

Additionally, this study finds that older Hispanics are concerned about how well their local health care services will accommodate their cultural needs, particularly long-term care services. Few Hispanics age 40 and older have confidence in the ability of local nursing homes and assisted living communities to meet these needs, though more say general practice doctors, home health care aides, hospitals, and health care specialists are up to the task.

The nationally representative survey of 1,341 adults age 40 and older includes an oversample of 310 Hispanics. Interviews were conducted between March 2 and March 29, 2017 on NORC’s AmeriSpeak® Panel.

By focusing on the experiences of Hispanics age 40 and older in their encounters with the health care system, their feelings about these experiences, and their expectations for how well the health care system is set up to accommodate their cultural needs, this study provides the perspective of a critical group of Americans as the country shapes its approach to addressing the mounting long-term care needs of the population.

Key findings include:

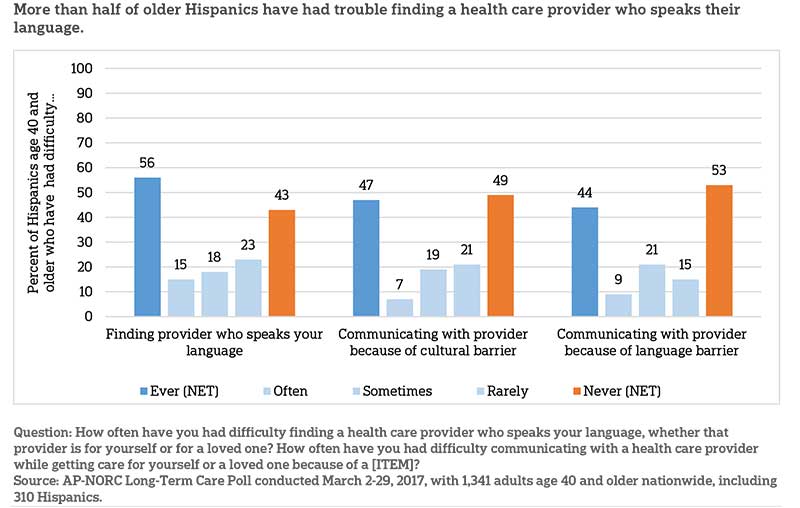

- More than half of Hispanics age 40 and older have had difficulty finding a health care provider for themselves or a loved one who speaks their language, with 15 percent saying this has often been a problem.

- About half have had difficulty communicating with a health care provider because of a cultural barrier (47 percent) or language barrier (44 percent).

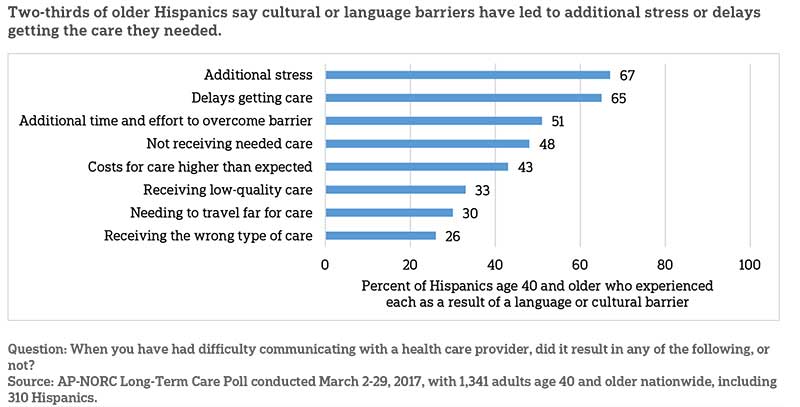

- Of those who have experienced cultural or language barriers in the health care system, two-thirds say it has resulted in additional stress or delays in getting care. Half say it resulted in additional time and effort to find resources to overcome that barrier.

- Less than a quarter of Hispanics age 40 and older are confident that local home health aides (20 percent), assisted living communities (18 percent), or nursing homes (16 percent) can accommodate their cultural needs.

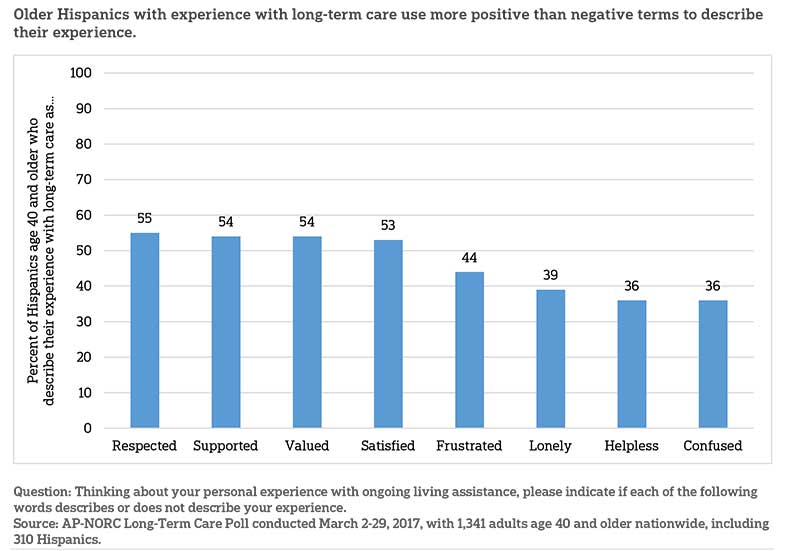

- More than half of older Hispanics with long-term care experience say they felt respected, valued, supported, or satisfied during their time either providing or receiving care, though more than a third also say they felt frustrated, lonely, confused, or helpless.

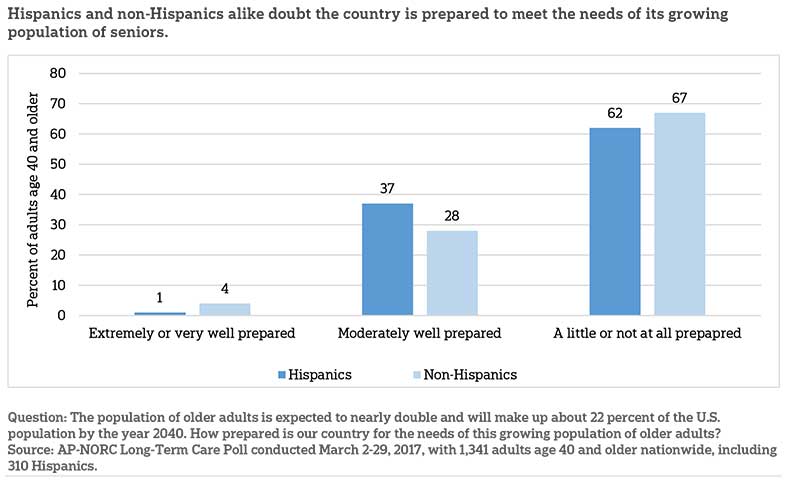

- Similar to adults overall, 62 percent of Hispanics age 40 and older say the United States is not well prepared to meet the needs of its aging population.

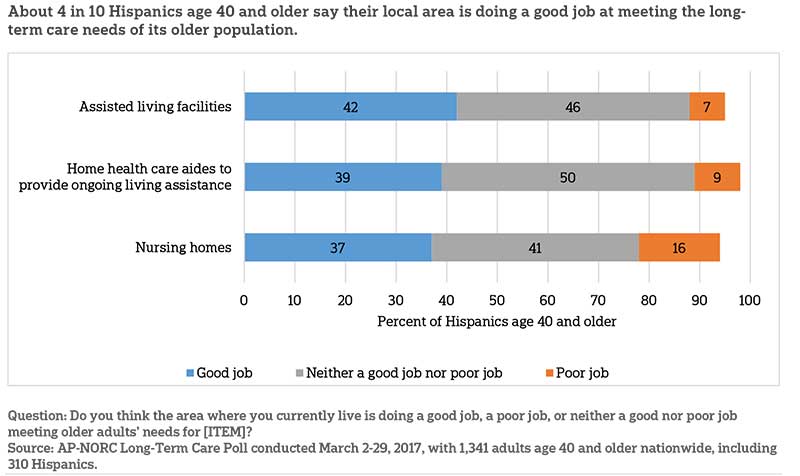

- About 4 in 10 older Hispanics say their local area is doing a good job of providing assisted living facilities (42 percent), home health aides (39 percent), and nursing homes (37 percent) to meet the ongoing living assistance needs of its seniors.

Many Older Hispanics Have Faced Language and Cultural Barriers While Navigating the Health Care System.ꜛ

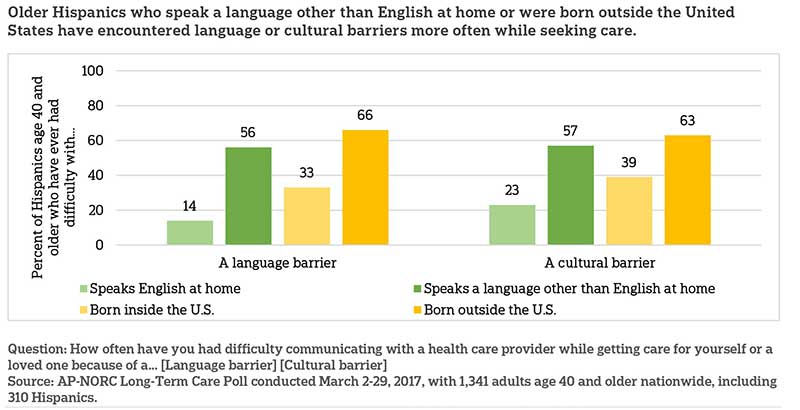

As of 2015, nearly 3 in 4 Hispanics in the United States speak Spanish at home, and 33 percent say they speak English less than “very well.”5 When seeking care for themselves or a loved one, more than half (56 percent) of all Hispanics age 40 and older report they have had difficulty finding a health care provider who speaks their language, and 15 percent say this problem occurs often. Older Hispanics who speak a language other than English at home are even more likely to encounter obstacles finding a provider who speaks their language, with 67 percent saying they have had difficulties.

Similarly, just under half of Hispanics age 40 and older say they have had difficulty communicating with a health care provider while getting care for themselves or a loved one because of either a language barrier (44 percent) or a cultural barrier (47 percent). Nine percent say they encounter language barriers often, and 7 percent report frequently having difficulty due to cultural barriers. Many have encountered these difficulties when getting care for a loved one (66 percent), though some also have experienced them when getting care themselves (28 percent).

These barriers are particularly pronounced for those who were born outside the United States, estimated to be 39 percent of the U.S. Hispanic population,6 and those who speak a language other than English at home.

More often than not, these cultural and language obstacles have emotional and financial impacts on those who encounter them. Two-thirds (67 percent) of older Hispanics say these barriers resulted in additional stress, and half (51 percent) required additional time and effort to find resources to overcome the barrier. Thirty percent say they had to travel far for care as a result of the barrier.

Beyond the extra stress and resources required to obtain care, older Hispanics report these language and cultural barriers have resulted in lower-quality, more expensive medical care. Sixty-five percent of Hispanics age 40 and older who experienced a barrier say it resulted in delays in getting care, and 48 percent say it led to not receiving the care needed. Another 43 percent say it led to higher-thanexpected costs, 33 percent say it led to low-quality care, and 26 percent received the wrong type of care entirely.

Older Hispanics Lack Confidence That the Long-term Care Services in Their Area Can Accommodate Their Cultural Needs.ꜛ

When it comes to meeting the cultural needs of older Hispanics, most do not feel confident that the long-term care services and other health care providers nearby can adequately accommodate them.

Few Hispanics age 40 and older say they are extremely or very confident that local nursing homes (16 percent) and assisted living communities (18 percent) can meet their needs, while 4 in 10 have little confidence or none at all in each. Older Hispanics who describe their overall health as fair or poor are much less likely than those who say their health is good or better to be confident in the cultural accommodations of nursing homes (5 percent vs. 22 percent) or assisted living (7 percent vs. 23 percent) in their area.

More have confidence in the cultural competence of hospitals and local health care specialists. About a third (34 percent) of older Latinos are extremely or very confident in their local hospitals’ ability to accommodate their cultural needs, and 32 percent say the same about health care providers who specialize in a specific type of care, like a cardiologist or orthopedist. Just under half are somewhat confident about each. Few express low confidence.

Confidence in general practice doctors and home health aides is more mixed. Among older Hispanics, 29 percent are confident in local general practitioners’ abilities to account for their cultural needs, but nearly as many say they are not confident (23 percent). Older Hispanics are even less confident in home health care aides’ cultural competence, with a third saying they are not too or not confident at all.

Despite Obstacles, Most Older Hispanics Report Positive Feelings about Their Experiences with Long-term Care.ꜛ

Forty-five percent of Hispanics age 40 and older report experience with long-term care as either a recipient, a caregiver, or by paying for care. Among this group, most cite positive feelings about their experience. More than half say they felt respected, valued, supported, and satisfied during their experience. But many also described their experience as frustrating, and fewer, but still more than a third, say they felt lonely, confused, or helpless.

Older Hispanics Do Not Think the United States Is Prepared to Meet the Needs of Its Seniors, but More Say Their Local Area Is Doing a Good Job.ꜛ

With seniors expected to make up 22 percent of the U.S. population by 2040,7 Hispanics age 40 and older, like non-Hispanics, say the country is not well prepared to meet the needs of this growing group of older adults. Sixty-two percent say the country is only a little or not at all prepared, while 37 percent say it is moderately prepared and just 1 percent say it is very well or extremely prepared.

Older Hispanics’ evaluations of the services in their local area are more positive. About 4 in 10 older Hispanics say their local area is doing a good job of providing assisted living facilities, home health aides, and nursing homes to meet the ongoing living assistance needs of its seniors. But higher numbers say their local area is doing neither a good nor poor job of providing these services. Few say their area is doing a poor job.

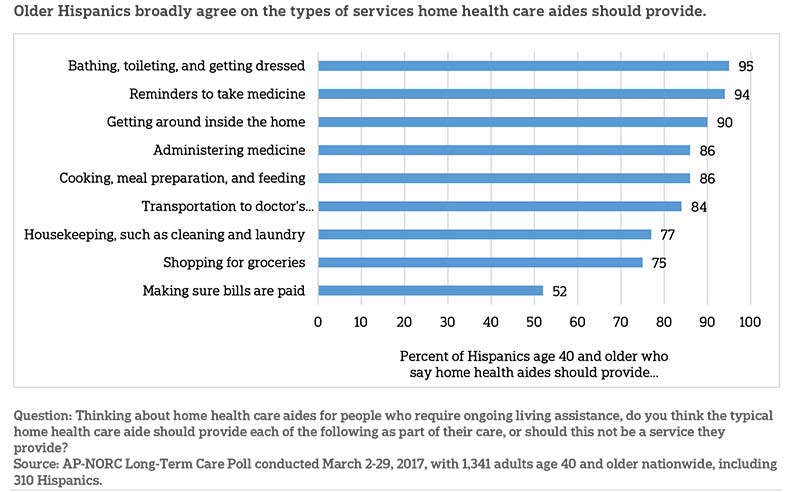

Older Hispanics broadly agree on many of the tasks home health care aides should perform. And while Hispanics evaluate the role of home health aides similarly to non-Hispanics, some differences do emerge. Hispanics age 40 and older are more likely to say they should shop for groceries (75 percent vs. 60 percent) and manage bills to make sure they are getting paid (52 percent vs. 31 percent) than non-Hispanics age 40 and older.

Eighty-six percent of older Hispanics also say home health aides should help with administering medicine to those in their care. In many states, however, home health aides are only allowed to remind those in their care to take medications, not actually administer medications themselves.8

About the Studyꜛ

Study Methodology

This study, funded by The SCAN Foundation, was conducted by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. Data were collected using AmeriSpeak®, NORC’s probability-based panel designed to be representative of the U.S. household population. During the initial recruitment phase of the panel, randomly selected U.S. households were sampled with a known, non-zero probability of selection from the NORC National Sample Frame and then contacted by U.S. mail, email, telephone, and field interviewers (face-to-face). The panel provides sample coverage of approximately 97% of the U.S. household population. Those excluded from the sample include people with P.O. Box only addresses, some addresses not listed in the USPS Delivery Sequence File, and some newly constructed dwellings. Staff from NORC at the University of Chicago, The Associated Press, and The SCAN Foundation collaborated on all aspects of the study.

Interviews for this survey were conducted between March 2 and March 29, 2017, with adults age 40 and older representing the 50 states and the District of Columbia. Panel members were randomly drawn from AmeriSpeak, and 1,341 completed the survey—1,106 via the web and 235 via telephone. The sample also included an oversample of Hispanic adults—310 Hispanics age 40 and older. Interviews were conducted in both English and Spanish, depending on respondent preference. Respondents were offered a small monetary incentive ($3) for completing the survey.

The final stage completion rate is 37.2 percent, the weighted household panel response rate is 34.4 percent, and the weighted household panel retention rate is 94.7 percent, for a cumulative response rate of 12.1 percent. The overall margin of sampling error is +/- 4.0 percentage points at the 95 percent confidence level, including the design effect. For the oversample of Hispanics, the margin of sampling error at the 95 percent confidence level is +/- 9.2 percentage points.

Once the sample has been selected and fielded, and all the study data have been collected and made final, a poststratification process is used to adjust for any survey nonresponse as well as any noncoverage or under- and oversampling resulting from the study-specific sample design. Poststratification variables included age, gender, census division, race/ethnicity, and education. Weighting variables were obtained from the 2016 Current Population Survey. The weighted data reflect the U.S. population of adults age 18 and over.

In 2013-2016, interviews were conducted through a random digit dial telephone survey on landlines and cell phones with samples of adults age 40 and older. The trend findings should be considered, keeping in mind the mode change from the telephone surveys in prior years of the poll to the mixed web and telephone method using the AmeriSpeak Panel for the 2017 poll.

All analyses were conducted using STATA (version 14), which allows for adjustment of standard errors for complex sample designs. All differences reported between subgroups of the U.S. population are at the 95 percent level of statistical significance, meaning that there is only a 5 percent (or less) probability that the observed differences could be attributed to chance variation in sampling. Additionally, bivariate differences between subgroups are only reported when they also remain robust in a multivariate model controlling for other demographic, political, and socioeconomic covariates.

A comprehensive listing of all study questions, complete with tabulations of top-level results for each question, is available on The AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research long-term care website: www.longtermcarepoll.org.

Contributing Researchers

From NORC at the University of Chicago

Jennifer Benz

Dan Malato

Jennifer Titus

Liz Kantor

Trevor Tompson

From The Associated Press

Emily Swanson

About the Associated Press-norc Center for Public Affairs Research

The AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research taps into the power of social science research and the highest-quality journalism to bring key information to people across the nation and throughout the world.

- The Associated Press (AP) is the world’s essential news organization, bringing fast, unbiased news to all media platforms and formats.

- NORC at the University of Chicago is one of the oldest and most respected, independent research institutions in the world.

The two organizations have established The AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research to conduct, analyze, and distribute social science research in the public interest on newsworthy topics, and to use the power of journalism to tell the stories that research reveals.

The founding principles of The AP-NORC Center include a mandate to carefully preserve and protect the scientific integrity and objectivity of NORC and the journalistic independence of AP. All work conducted by the Center conforms to the highest levels of scientific integrity to prevent any real or perceived bias in the research. All of the work of the Center is subject to review by its advisory committee to help ensure it meets these standards. The Center will publicize the results of all studies and make all datasets and study documentation available to scholars and the public.

Footnotesꜛ

1. Administration on Aging, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2016. A Profile of Older Americans: 2016. https://www.acl.gov/sites/default/files/Aging%20and%20Disability%20in%20America/2016-Profile.pdfꜛ

2. Administration on Aging, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2017. The Basics. http://longtermcare.gov/the-basics/ꜛ

3. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2016. Long-Term Services and Supports for Older Americans: Risks and Financing Research Brief. https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/long-term-services-and-supports-older-americans-risks-and-financing-research-briefꜛ

4. U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce. 2015. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdfꜛ

5. U.S. Bureau of the Census. 2015. 2015 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_14_5YR_B16005I&prodType=tableꜛ

6. U.S. Bureau of the Census. 2015. 2015 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_14_5YR_B16005I&prodType=tableꜛ

7. Administration on Aging, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2016. A Profile of Older Americans: 2016. https://www.acl.gov/sites/default/files/Aging%20and%20Disability%20in%20America/2016-Profile.pdfꜛ

8. S.C. Reinhard, E. Kassner, A. Houser, K. Ujvari, R. Mollica, and L. Hendrickson. 2014. Raising Expectations, 2014: A State Scorecard on Long-Term Services and Supports for Older Adults, People with Physical Disabilities, and Family Caregivers. AARP, Commonwealth Fund, and SCAN Foundation. http://www.longtermscorecard.org/2014-scorecardꜛ