© 2013 AP Photo/Darron Cummings

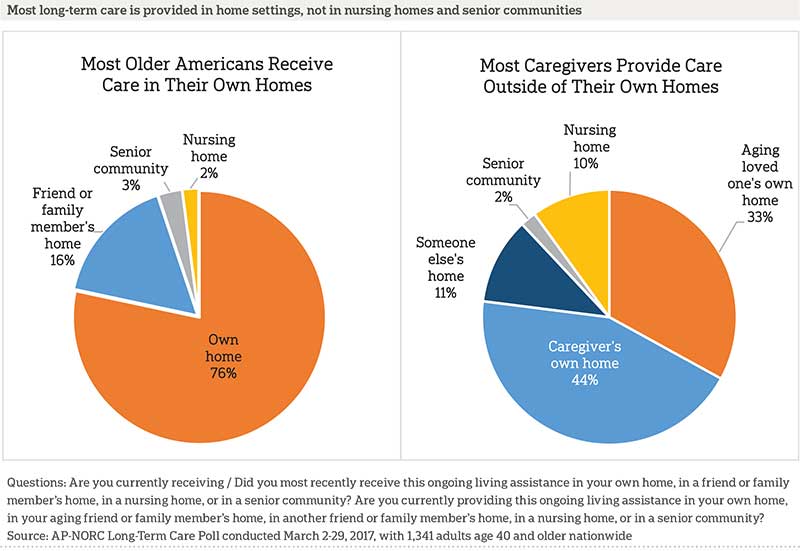

Results from the 2017 Long-Term Care trends poll find that two-thirds of Americans age 40 and older feel the country is not prepared for the rapid growth of the older adult population. The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research survey also finds that at the local level, less than half of older Americans say their community is doing a good job of meeting older adults’ needs for nursing homes, assisted living facilities, and home health care aides to provide long-term care. Additionally, a majority of older adults say they would like the federal government to devote a lot or a great deal of effort this year to helping people with the costs of ongoing living assistance.

The population of Americans age 65 and older is growing at an unprecedented rate. In 2014, there were 46.2 million adults age 65 and older, and this number is expected to more than double to comprise about 98 million older adults by the year 2060.1 The majority of these older adults will require at least some support with activities of daily living as they age—things like cooking, bathing, or remembering to take medicine.2,3

For many, long-term services and supports are provided informally, within the home, by unpaid family and friends acting as caregivers. These informal caregivers face high costs for providing care, including lost income and increased stress, and often feel unprepared for the role. When informal networks of families and friends are unable to cover all of a person’s care needs, paid long-term care services—including home health care aides, assisted living communities, and nursing homes—help to fill the gap. Long-term care services such as these bring high costs, not only to individuals in need of care and their families but also to taxpayers and the government.

To help policymakers, health care systems, and families address this issue, research conducted by The AP-NORC Center examines awareness of older Americans’ understanding of the long-term care system, their perceptions and misperceptions regarding the likelihood of needing long-term care services and the cost of those services, and their attitudes and behaviors regarding planning for long-term care.

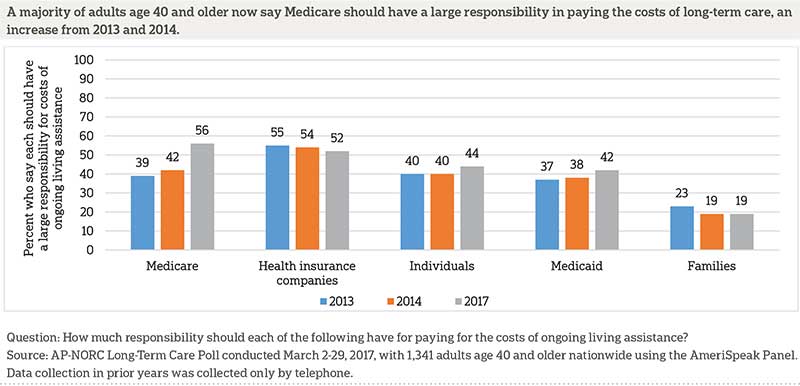

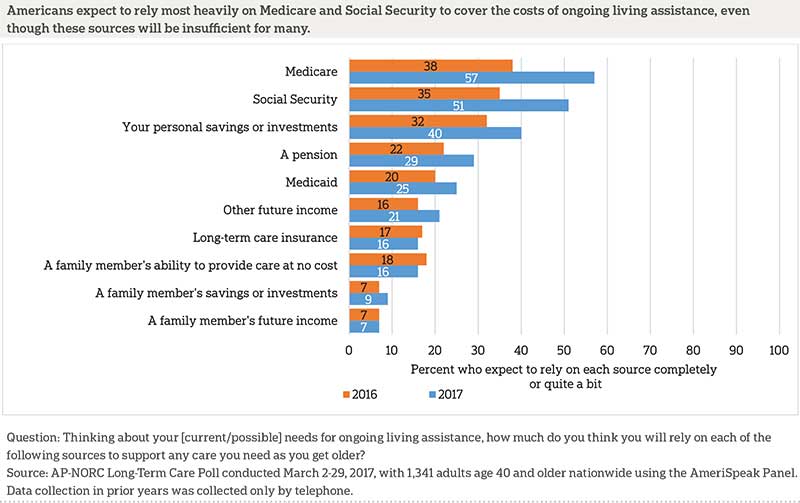

Americans are confused about how they might pay for any needed care. The source that most Americans age 40 and older expect to rely heavily on to pay for ongoing living assistance is Medicare, which 57 percent say they will rely on quite a bit or completely. However, Medicare does not cover many expenses associated with long-term care, including most care in nursing homes, assisted living facilities, or from home health care aides.4 When it comes to who should ideally be responsible for paying for long-term care, over half of older adults believe that Medicare (56 percent) and health insurance companies (52 percent) should pay these costs. About 4 in 10 say that it should be the responsibility of individuals (44 percent) and Medicaid (42 percent) to pay for these costs.

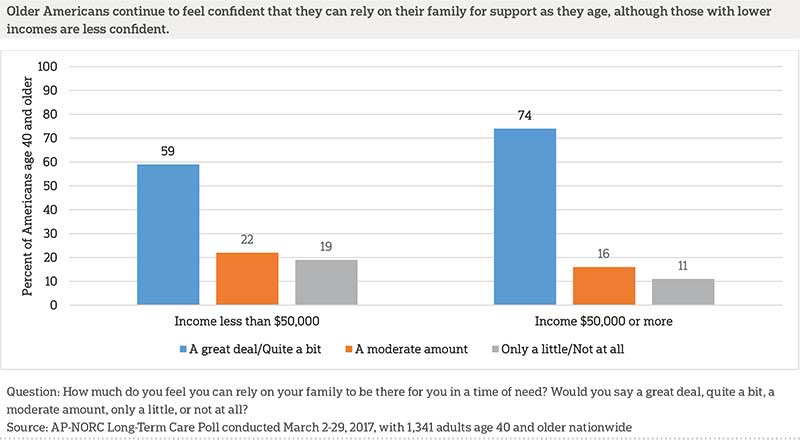

Americans continue to feel confident that they can rely on their family for support as they age. More than two-thirds of those age 40 and older say they feel they can rely on their family a great deal or quite a bit, 18 percent say they can rely on their family a moderate amount, and 14 percent say they can rely on them only a little or not at all. Few, however, say that family members should have a substantial role in paying for long-term care. Just 19 percent believe that families should have a large responsibility for paying these costs.

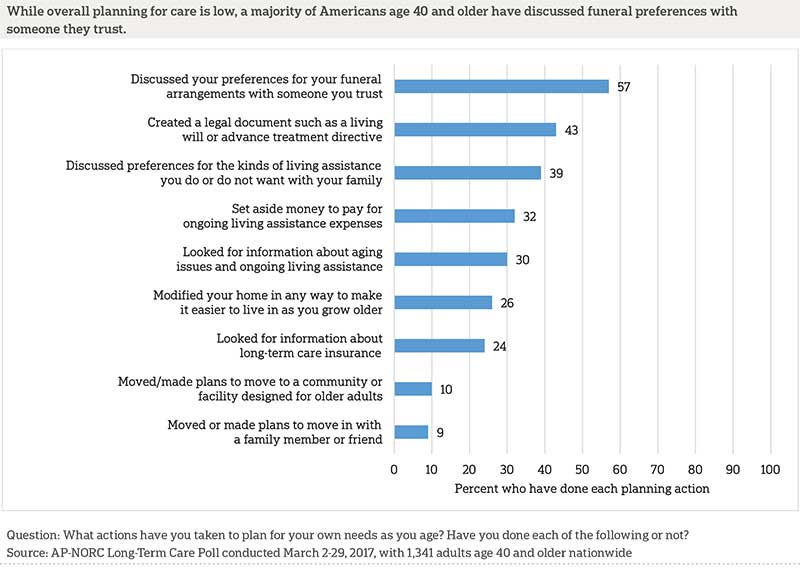

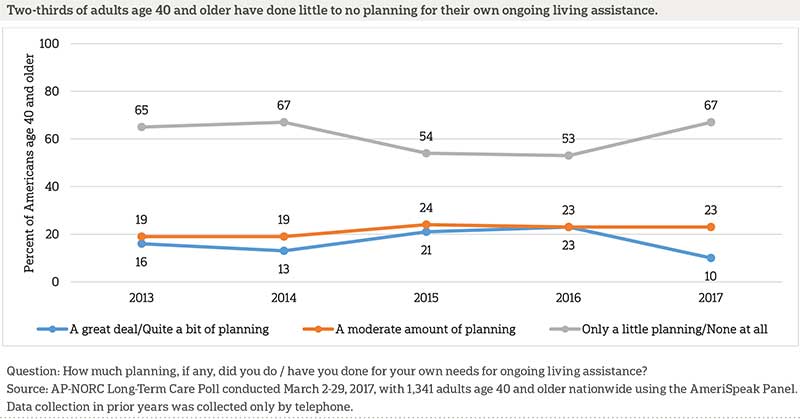

Overall, older Americans have not done much planning for their future or current needs for ongoing assistance. Two-thirds (67 percent) say they have done only a little or no planning at all for their own needs. About a quarter (23 percent) say they have done a moderate amount of planning, and just 1 in 10 say they have done a great deal or quite a bit of planning.

Since 2013, The AP-NORC Center has conducted annual surveys to investigate experiences and attitudes regarding long-term care.5 These surveys have revealed that a majority of American adults age 40 and older hold several misperceptions about the extent of the long-term care services they are likely to need in the future and about the cost of those services. Few older Americans have done substantial planning or saving for their future needs, and less than half have even talked about the topic with their family. A majority support a variety of policy changes that would help in the financing of long-term care, as well as supporting changes in practice that favor a person-centered care approach.

The 2017 survey continues to track items from the previous years while also exploring new topics, including perceptions of the role of home health care aides in providing care, ratings of long-term care services in the local community, attitudes about the country’s preparedness to address the needs of the growing population of older adults, support for new policy proposals to help caregivers, and how much effort the federal government should devote to helping with long-term care costs.

To continue contributing new and actionable data to inform policymakers and the public about older Americans’ understanding of and experiences with long-term care, The AP-NORC Center, with funding from The SCAN Foundation, conducted a study including 1,341 interviews with a nationally representative sample of Americans age 40 and older from the AmeriSpeak® Panel.

Key findings from this study are described below:

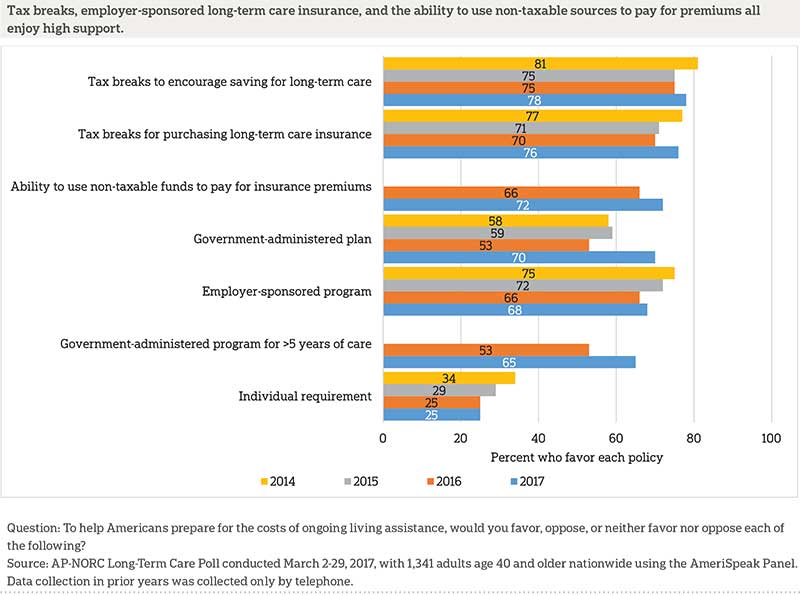

- Many favor tax breaks to encourage savings for long-term care (78 percent) or for purchasing long-term care insurance (76 percent), as well as the ability to use non-taxable funds like IRAs or 401(k)s to pay for long-term care insurance premiums (72 percent) and a COBRA-like long-term care insurance plan that individuals can purchase through their employer (68 percent). Fewer, however, support a government requirement that individuals purchase private long-term care insurance (25 percent).

- Seventy percent of older Americans support a government-administered long-term care insurance program, similar to Medicare, a significant jump from the 53 percent who said the same in 2016. Additionally, 65 percent favor a government-administered long-term care insurance program that would specifically cover people who require care for more than five years. This is also a significant increase from the 53 percent who favored such a program in 2016.

- Overall, a little more than half (52 percent) of Americans age 40 and older say they have heard of paid family leave programs, and a little less than half (48 percent) have not. Those in the three states currently operating paid family leave programs are more likely than those in other states to be aware of such programs (71 percent vs. 48 percent).

- Support for paid family leave programs is widespread among older Americans, even among those not previously aware of them and those who live in states where they have yet to be implemented. More than three-quarters (76 percent) of older Americans say they would favor such a policy in their state. Those who have heard of such programs are more likely than those who have not to favor them, but support is high among both groups (82 percent vs. 71 percent).

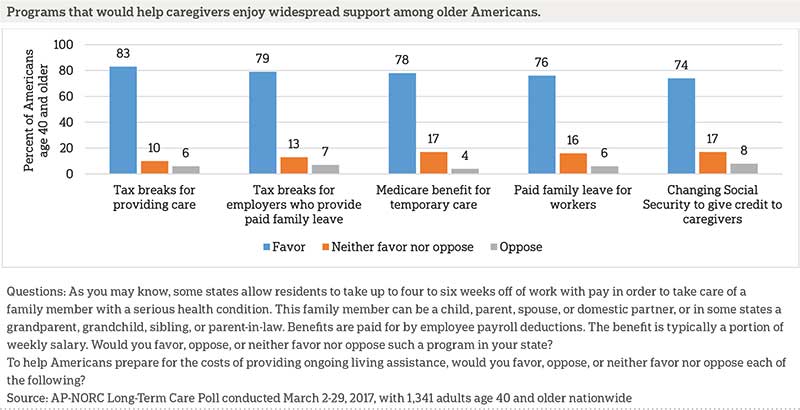

- More than 8 in 10 Americans age 40 and older favor tax breaks for people who provide care to a family member, and three-quarters or more approve of tax breaks for employers who provide paid family leave (79 percent), a Medicare benefit that provides temporary respite care (78 percent), and changing Social Security rules to give earnings credits to caregivers who leave the workforce to care for a family member (74 percent).

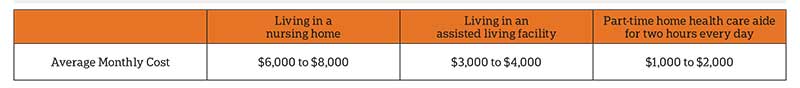

- Only about a quarter are able to correctly estimate the national average monthly cost of living in a nursing home (26 percent), living in an assisted living facility (25 percent), and hiring a part-time home health care aide (29 percent).

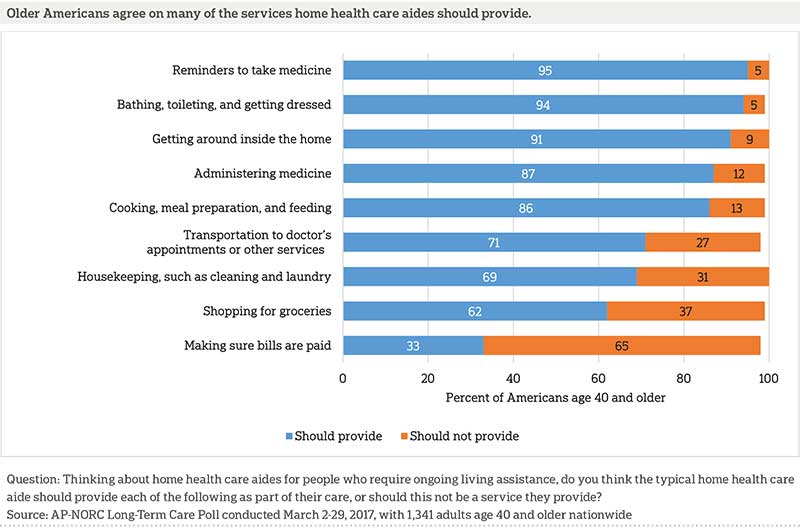

- There is general agreement that home health aides should provide those in their care with reminders to take medicine; support with bathing, toileting, and getting dressed; help getting around inside the home; and help with cooking, meal preparation, and feeding. A majority also say that transportation to appointments, housekeeping, and shopping for groceries should be included as typical services provided by home health aides. Fewer (33 percent) say they should help make sure bills are paid.

- Nearly 9 in 10 say home health aides should administer medicines to persons in their care, though whether this service is allowed varies by state.

- Those with long-term care experience are more likely than those without such experience to say their local area does a good job meeting older adults’ needs for home health care aides (48 percent vs. 35 percent) and nursing homes (43 percent vs. 33 percent).

- Women are more likely than men to say their local area does a poor job when it comes to meeting older adults’ needs for home health care aides (10 percent vs. 5 percent) and nursing homes (15 percent vs. 9 percent).

- Six in 10 think it is at least somewhat likely that an aging family member or close friend will need long-term care in the next five years, and over half expect to be at least partially responsible for providing that care themselves.

- Only 12 percent of prospective caregivers feel very or extremely prepared to take on a caregiving role. Over half say they feel somewhat prepared to provide this support, and about a third say they feel not too or not at all prepared to provide care to their loved ones in the near future.

- Those who are currently employed are much more likely to say they feel not too or not at all prepared to provide care to loved ones in the next five years compared to those who are not employed (40 percent vs. 22 percent).

Additional information, including the survey’s complete topline findings, can be found on The AP-NORC Center’s long-term care project website at www.longtermcarepoll.org.

Many Expect to Need Long-term Care Eventually, but Few Older Adults Think Their Local Community or the Country Is Prepared to Meet That Need.ꜛ

As in recent years, older Americans slightly underestimate the likelihood they will need long-term care in the future.

Nearly two-thirds of Americans age 40 and older expect they will need help as they age, while government statistics show that 70 percent of people age 65 and older will need at least some form of long-term care and 50 percent will need extensive services.6,7 Nineteen percent think it is very or extremely likely they will need care in the future, 45 percent think it is somewhat likely, while 35 percent think it is not too or not at all likely.

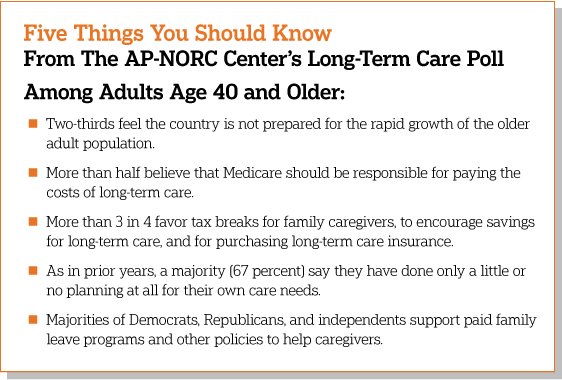

Fully two-thirds say the country is not at all or only a little prepared to meet the needs of the growing population of older adults.8 Twenty-nine percent say the United States is moderately prepared to meet these needs, while only 4 percent believe the country is very well or extremely prepared.

Views on the country’s preparedness vary based on gender and level of education. Women are more concerned than men, with 37 percent of women saying that the country is not at all prepared compared to 29 percent of men. Those with at least some college are more likely than those with a high school degree or less education to say the United States is only a little or not at all prepared to accommodate the growth in the population of older adults in the country (73 percent vs. 58 percent).

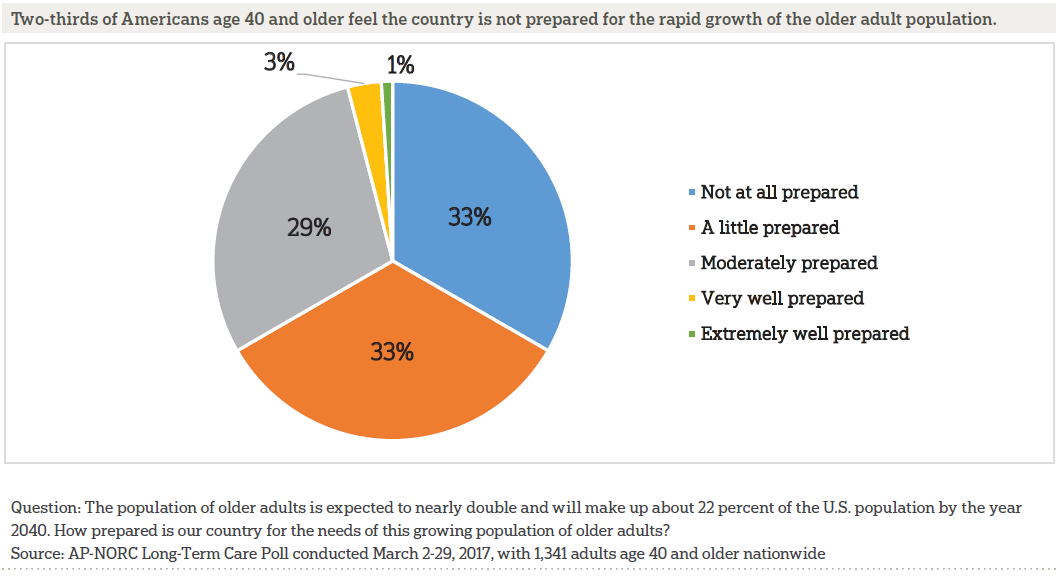

At the local level, less than half of Americans age 40 and older say their local community is doing a good job of meeting older adults’ needs for nursing homes, assisted living facilities, and home health care aides to provide ongoing living assistance.

Assessments of the local area’s ability to meet the long-term care needs of older adults for home health care aides and nursing homes differ by past experience with long-term care and gender.

Most notably, those with any experience with long-term care themselves9 rate their local community’s ability to meet some of these needs more positively than do those who have neither received nor provided long-term care in the past. Those with long-term care experience are more likely than those without such experience to say their local area does a good job of meeting older adults’ needs for home health care aides (48 percent vs. 35 percent) and nursing homes (43 percent vs. 33 percent).

Women, who are both more likely to need long-term care and more likely to act in the role of caregiver to someone else,10 are more negative than men in their assessments of their local community’s ability to meet older adults’ needs for some of these services. Ten percent of women say their local area does a poor job when it comes to home health care aides, compared to 5 percent of men. Conversely, men are more likely than women to say their local area does a good job when it comes to home health care aides (46 percent vs. 37 percent). Finally, 15 percent of women say their local area does a poor job when it comes to nursing homes, compared to 9 percent of men.

Those with and without long-term care experience give similar ratings when it comes to their local community’s ability to meet older adults’ needs for assisted living facilities, as do men and women.

When They Do Need Long-term Care, Most Older Americans Rely on Their Friends and Family Members to Provide That Care at Home.ꜛ

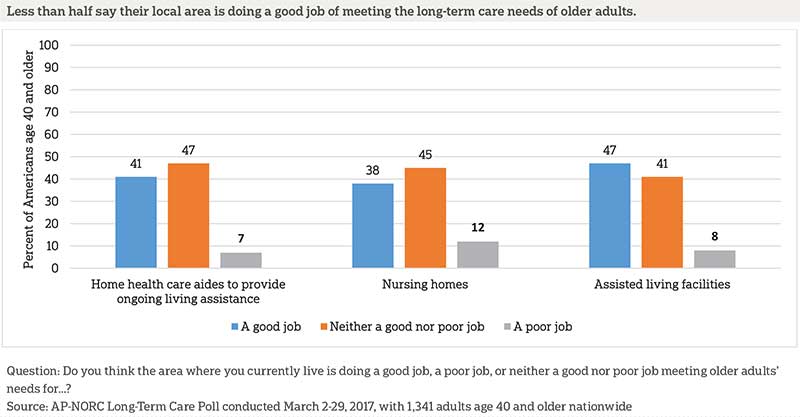

About half of older Americans have some type of experience with long-term care, including as a care provider, as a recipient of care themselves, or by employing someone else to provide care in their family. Altogether, 40 percent have past or current experience providing long-term care to a family member or close friend, 7 percent have personal experience receiving care either currently or in the past, and 7 percent say their family currently employs someone to provide in-home health services.

For most older adults with experience with long-term care, that care was provided in a home setting, not in a nursing home or senior community.

Nine in 10 of those with personal experience receiving care report that the care was provided in their own home or a friend or family member’s home. Just 5 percent received care in another setting. Among those with personal experience receiving care in a home setting, the majority received that care from a caregiver who was a family member or friend, not a paid professional. Over half received care from a family member, 20 percent received care from a friend, and 28 percent received care from a professional home health care aide.

Nearly 9 in 10 of those with current experience providing care report that the care was provided in a home setting.

Among older Americans who are not currently providing long-term care to someone else, 6 in 10 think it is at least somewhat likely that an aging family member or close friend will need this type of support in the next five years. Over half of those with a loved one who will need assistance in the coming years expect to be at least partially responsible for providing that care themselves.

However, few feel adequately prepared to take on a caregiving role. Only 12 percent of these prospective caregivers feel very or extremely prepared to provide this support. Over half feel somewhat prepared to become a caregiver, and about a third feel not too or not at all prepared to provide care to their loved ones in the near future. Those who are currently employed are much more likely to feel not too or not at all prepared to provide care in the next five years compared to those who are not employed (40 percent vs. 22 percent).

Overall, older Americans continue to feel confident that they can rely on their family for support as they age. More than two-thirds of those age 40 and older say they feel they can rely on their family a great deal or quite a bit, 18 percent say they can rely on their family a moderate amount, and 14 percent say they can rely on them only a little or not at all.

Older adults with lower incomes are less sure they can rely on their family for support as they grow older compared to those with higher incomes.

Older Adults Mostly Agree on the Services Home Health Care Aides Should Provide.ꜛ

Among those who have received long-term care in a home setting, about 3 in 10 got this care from professional home health aides. Further, 7 percent say their family currently employs someone to provide in-home ongoing living assistance.

Asked about the scope of services they think home health aides should provide, Americans generally agree that aides should be able to support a range of supportive services from assistance with medications to transportation and grocery shopping. Most say home health care aides should provide those in their care with reminders to take medicine; support with bathing, toileting, and getting dressed; help getting around inside the home; and with cooking, meal preparation, and feeding. A majority also say that transportation to appointments, housekeeping, and shopping for groceries should be included as typical services that home health care aides provide.

In addition to these typical services, 87 percent say home health care aides should administer medicines to persons in their care. However, whether or not home health care aides are allowed to administer medication varies by state. In many states, home health care aides are prohibited from administering medications, and they may only assist people with taking their own medications by giving them reminders.11

When it comes to providing assistance with managing finances, one-third say making sure the care recipient is getting their bills paid is a service that home health care aides should provide, while two-thirds think they should not provide this type of service. Older adults with personal experience receiving long-term care are more likely than those without such experience to think home health care aides should provide this type of support (47 percent vs. 32 percent).

Few Have a Realistic Idea of the Actual Costs of Long-Term Care.ꜛ

Older Americans have a number of options when it comes to long-term care, such as moving into a nursing home, assisted living community, or hiring someone to assist with care, which come at varying costs. About 3 in 4 Americans age 40 and older have misperceptions about the price of their long-term care choices, frequently underestimating the cost of senior living arrangements in particular but overestimating costs for an in-home aide.

Nursing home care is the most expensive of three common options for ongoing living assistance.12

Overall, about a quarter of adults age 40 and older are able to correctly estimate the national average monthly cost of living in a nursing home, living in an assisted living facility, and hiring a part-time home health care aide.

Residence in a nursing home is the most expensive of the three options asked about—between $6,000 and $8,000 per month on average. This is also the most frequently underestimated, with a majority (54 percent) who say the average is less than $6,000. Just 18 percent overestimate the cost of nursing home care.

Similarly, 44 percent of Americans age 40 and older underestimate the cost of assisted living communities, which on average total $3,000 to $4,000 per month. Three in 10 overestimate this cost.

However, a majority of older Americans overestimate how much it costs to hire a home health care aide who visits for two hours every day, which on average costs $1,000 to $2,000 per month. Nearly 6 in 10 (59 percent) say it costs more than $2,000 per month, including some who drastically overestimate. Sixteen percent say this service costs more than $4,000 per month, more than double the actual national average.

In the past three years, the public has generally not improved its knowledge of the cost of long-term care, with 20 to 30 percent of adults age 40 and older correctly identifying the average cost of each long-term care option in 2013, 2014, and 2017. However, perceptions of the cost of assisted living communities and home health care aides have shifted slightly. In 2017, more older Americans underestimate the cost of an assisted living community (44 percent vs. 31 percent in both 2013 and 2014), and more now overestimate the cost of a home health care aide (59 percent vs. 51 percent in 2013 and 48 percent in 2014). Additionally, while these costs represent a monthly average nationwide, costs for long-term care services vary substantially by state and region. For example, in Texas the monthly average cost of nursing home care is just $4,440, while a nursing home in Massachusetts is more than $11,000 per month.13

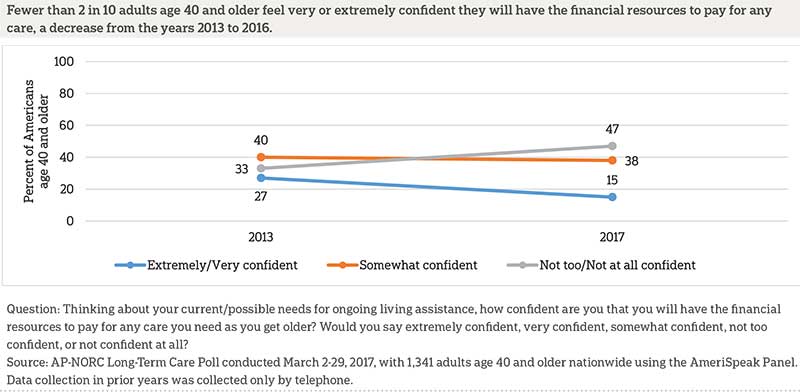

While already underestimating the costs of most care, only 15 percent of Americans age 40 and older are very or extremely confident that they will have the financial resources to pay for long-term care. Another 38 percent are somewhat confident, and 47 percent are not too confident or not confident at all about their financial resources to pay for care as they get older.

Older Americans are less confident in their ability to pay for long-term care now than in the past, representing a departure from an upward trend in 2013 to 2016. However, the decrease in 2017 may be partially explained by general feelings of uncertainty about health care issues during the debate over repealing the Affordable Care Act and replacing it with the American Health Care Act, which was prominently in the news when the survey was conducted.

Further, most older Americans continue to have not set aside money to pay for their current or future long-term care expenses, a trend that has remained stable since 2013. More than 2 in 3 (68 percent) adults age 40 and older have not reserved funds to pay for ongoing living assistance expenses, including nursing home care, senior community, or care from a home health care aide. About a third of older Americans have set aside money for long-term care expenses from 2013 to 2017.

Half of Older Americans Believe Medicare and Health Insurance Companies Should Be Responsible for Paying Long-term Care Costs.ꜛ

When it comes to who should ideally be responsible for paying for long-term care, over half of older adults believe that Medicare (56 percent) and health insurance companies (52 percent) should pay these costs. Another 4 in 10 say that it should be the responsibility of individuals (44 percent) and Medicaid (42 percent) to pay for these costs.

Fewer say that family members should have a substantial role in paying for long-term care. Just 19 percent believe that families should have a large responsibility for paying these costs.

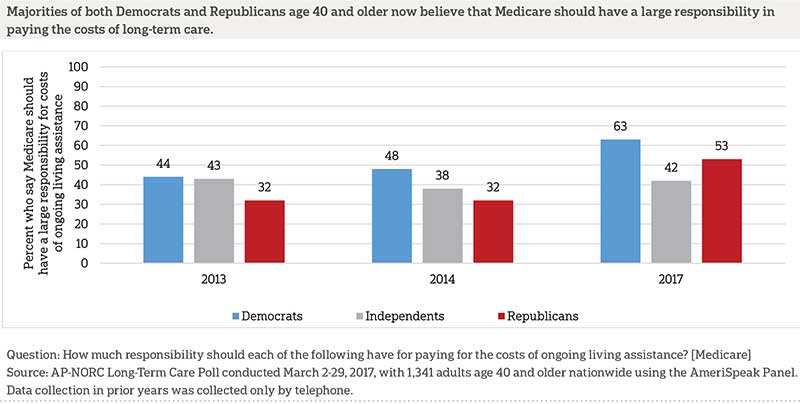

With the exception of Medicare, older Americans’ ideals for who should share the costs have changed little since 2013 and 2014. More adults age 40 and over now believe that Medicare should have a large responsibility to pay for the costs of ongoing living assistance.

Though these options could raise ideological or partisan cues, Democrats and Republicans are largely in agreement as to who should bear the brunt of costs for long-term care. Democrats are no more likely than Republicans to say government-based funding through both Medicare and Medicaid should have a major role; in 2017, partisans on both sides of the aisle have now coalesced around Medicare, with majority support from both Democrats and Republicans. However, support remains lower from independents.

Many Americans Expect to Rely on Medicare and Social Security to Pay for Their Long-Term Care Needs.ꜛ

With high costs of care, many Americans will need to—and expect to—rely on multiple sources to pay for ongoing living assistance as they get older. The source that most Americans age 40 and older expect to rely heavily on to pay for ongoing living assistance is Medicare, which 57 percent say they will rely on quite a bit or completely. However, Medicare does not cover many expenses associated with long-term care, including most care in nursing homes, assisted living facilities, or from home health care aides.14 Over half of older Americans say they expect to rely heavily on Social Security to cover long-term care costs, but the average Social Security payment of $1,348 per month does not meet the average cost of care for many long-term care services.15

Just 25 percent expect to rely heavily on Medicaid, even though Medicaid is the largest payer of formal long-term care services in the country.16 Instead, more expect to rely on their personal savings or investments (40 percent) or a pension (29 percent). Many also expect to pay out-of-pocket using other future income (21 percent). Few (16 percent) expect to rely on long-term care insurance.

A small minority expect to rely heavily on support from their family to cover the expenses of care. Nine percent say they will rely quite a bit or completely on a family member’s savings or investments and 7 percent will rely on a family member’s future income. Sixteen percent also expect a family member to provide care to them at no cost.

Expected reliance on many of these sources has increased since 2016.

A minority, but not insignificant, share of older Americans think their current health insurance would pay for ongoing living assistance services should they need them (22 percent).

Sixteen percent of older Americans say they expect to rely a lot on long-term care insurance to cover their ongoing living assistance expenses, and nearly as many (14 percent) say they currently have long-term care from a private insurance company. But among those who say they have it, a portion are not very confident that they do. About half of those who say they have long-term care insurance are very confident they do, while 20 percent are somewhat sure and another 20 percent are somewhat or very unsure. Overall, just 7 percent of older Americans say they have long-term care insurance and are very confident that they have it. This represents a decline from 2016, when 13 percent said they were very sure they had long-term care insurance.

Support for Several Long-Term Care Insurance Programs Has Increased since 2016.ꜛ

Over the past few years, politicians of both parties have proposed policies that would help families with providing care and preparing for possible care needs in the future. Americans age 40 and older are fairly enthusiastic about government doing something to address these issues, with more than half (56 percent) saying they would like the federal government to devote a lot or a great deal of effort this year to helping people with the costs of ongoing living assistance. Another 30 percent say they would like the government to devote a moderate amount of effort. Just 13 percent would like to see only a little or no effort at all.

Democrats are most likely to want the government to devote a lot of effort or more to helping people with the costs of ongoing living assistance (69 percent), and more than half of independents do also (56 percent). But, less than half of Republicans feel the same (39 percent). Hispanics (67 percent) are also more likely than whites (51 percent) to want the government to put a lot of effort into these issues. Those who describe their health as good or better are less likely to want the government to devote a lot of effort to helping people with ongoing living assistance costs than those who describe their health as fair or poor (52 percent vs. 69 percent).

Majorities of those age 40 and older support many individual policies to help people prepare for the costs of long-term care. Many favor tax breaks to encourage savings for long-term care (78 percent) or for purchasing long-term care insurance (76 percent), as well as the ability to use non-taxable funds like IRAs or 401(k)s to pay for long-term care insurance premiums (72 percent) and a COBRA-like long-term care insurance plan that individuals can purchase through their employer (68 percent). Fewer, however, support a government requirement that individuals purchase private long-term care insurance (25 percent). Support for the ability to use non-taxable funds to pay for insurance and tax breaks for those who purchase long-term care insurance have both increased modestly since 2016, though the latter’s level of support is in line with what has been seen in past years.

Many older Americans also support government-administered long-term care insurance programs, and the popularity of these programs has increased since 2016. Today, 70 percent of older Americans support a government-administered long-term care insurance program, similar to Medicare, a significant jump from the 53 percent who said the same last year. Additionally, 65 percent favor a government-administered long-term care insurance program that would specifically cover people who require care for more than five years, which is a longer period of time than is typically covered by private long-term care insurance. This is also a significant increase from the 53 percent who favored such a program in 2016.

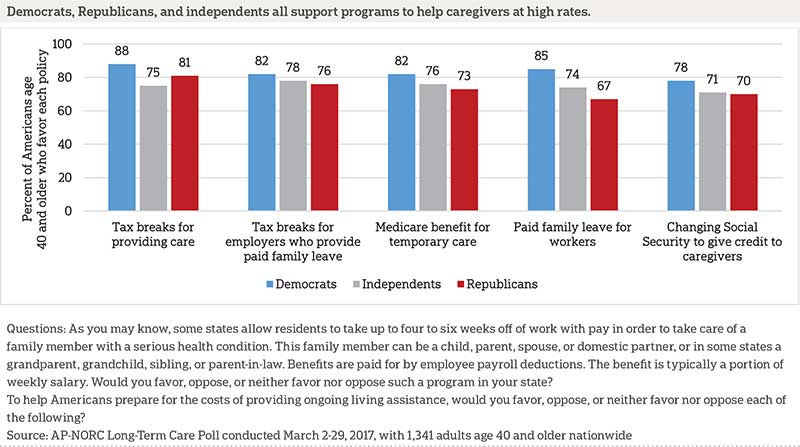

Support differs between Democrats, Republicans, and independents on several of these issues, with Democrats generally being most supportive. This is particularly the case when it comes to government-administered insurance programs. Though support for a government-administered program for long-term care insurance similar to Medicare is lowest among Republicans, it still receives majority support. Eighty-three percent of Democrats favor such a program compared to 69 percent of independents and 54 percent of Republicans. Similarly, 78 percent of Democrats support a government-administered program to specifically cover people who require care for more than five years versus 57 percent of independents and 54 percent of Republicans. And, while support is low across parties for an individual requirement to purchase long-term care insurance, more Democrats (33 percent) than Republicans (17 percent) favor one.

Paid Family Leave and Other Proposals to Help Alleviate the Costs Facing Caregivers Enjoy High Levels of Support.ꜛ

Currently, three states—California, New Jersey, and Rhode Island—operate paid family leave programs that allow residents to take time off to care for a family member in need while still receiving a portion of their salary. New York State and Washington, DC, also recently passed paid family leave programs that will take effect in the coming years.17 The federal government has no such program at the present time, but on the campaign trail in 2016 and on Capitol Hill, many politicians have expressed support for paid family leave programs at the national level, as well.18,19,20,21

Overall, a little more than half (52 percent) of Americans age 40 and older say they have heard of paid family leave programs, and a little less than half (48 percent) have not. Those in the three states currently operating paid family leave programs are more likely than those in other states to be aware of such programs (71 percent vs. 48 percent).

Support for paid family leave programs is widespread among older Americans, even among those not previously aware of them and those who live in states where they have yet to be implemented. More than three-quarters (76 percent) of older Americans say they would favor such a policy in their state, with little difference between those living in California, New Jersey, or Rhode Island and those living elsewhere. Those who have heard of paid family leave programs are more likely than those who have not to favor them, but support is high among both groups (82 percent vs. 71 percent). Support for paid family leave has increased modestly since 2016, rising about 4 percentage points from 72 percent last year.

Those with experience providing care and those with any experience with long-term care are no more likely than those without such experience to support paid family leave programs, but differences do emerge along partisan lines and by gender. While about half of Democrats, independents, and Republicans have heard of these programs and support is high among all three groups, Democrats are most supportive of them, with 85 percent saying they are in favor compared to 74 percent of independents and 67 percent of Republicans. Women are also more likely than men to have both heard of (56 percent vs. 47 percent) and support (80 percent vs. 72 percent) paid family leave.

Other programs designed to help Americans prepare for the costs of providing ongoing living assistance also enjoy high levels of support. More than 8 in 10 Americans age 40 and older continue to favor tax breaks for people who provide care to a family member, and more than three-quarters approve of tax breaks for employers who provide paid family leave to workers (79 percent) or a Medicare benefit that provides temporary care if the caregiver and care recipient live together and are both Medicare beneficiaries (78 percent). Nearly three-quarters (74 percent) continue to favor changing Social Security rules to give earnings credits to caregivers who leave the workforce in order to provide care to a family member. These programs have all been discussed at either the federal or state level.22,23

Majorities of Democrats, independents, and Republicans support all these policies, but Democrats are more likely than Republicans to favor changing Social Security so that caregivers who leave the workforce still earn credit (78 percent vs. 70 percent) and a Medicare benefit to provide temporary care when both the caregiver and recipient live together and are Medicare beneficiaries (82 percent vs. 73 percent).

Those who do not have experience providing care are just as supportive of these policies as those who are currently providing care or have in the past.

Reports of Planning for Long-term Care Needs Remain Low Overall.ꜛ

Overall, older Americans have not done much planning for their future or current needs for ongoing assistance. Two-thirds (67 percent) say they have done only a little or no planning at all for their own needs. About a quarter (23 percent) say they have done a moderate amount of planning, and just 1 in 10 say they have done a great deal or quite a bit of planning.

This year’s results show a decline from the rising levels of planning in 2015 to 2016. Still, in 2015 and 2016, majorities said they had done little to no planning for their long-term care needs.

Older Americans may take a number of actions to prepare for their future needs, such as discussing preferences with family, researching long-term care insurance, or making plans to move into a senior community. Overall, fewer adults age 40 and older have taken at least one of these actions in 2017 than in previous years. Eighty-two percent of older adults took at least one action to plan for ongoing living assistance, compared to 86 percent in 2016, 85 percent in 2014, and 85 percent in 2013.

Further, the most common action taken by older Americans is more about end-of-life decisions rather than planning for care. Fifty-seven percent report discussing preferences for funeral arrangements with a trusted person. Similarly, about 4 in 10 have created a living will or discussed preferences for ongoing living assistance with family. Three in 10 have set aside money for ongoing expenses or looked for information about aging issues and living assistance. Fewer have modified their home to make it easier as they grow older, looked for extra information about long-term care insurance, or made plans to move into a senior facility or with a family member.

About the Studyꜛ

Study Methodology

This study, funded by The SCAN Foundation, was conducted by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. Data were collected using AmeriSpeak®, NORC’s probability-based panel designed to be representative of the U.S. household population. During the initial recruitment phase of the panel, randomly selected U.S. households were sampled with a known, non-zero probability of selection from the NORC National Sample Frame and then contacted by U.S. mail, email, telephone, and field interviewers (face-to-face). The panel provides sample coverage of approximately 97% of the U.S. household population. Those excluded from the sample include people with P.O. Box only addresses, some addresses not listed in the USPS Delivery Sequence File, and some newly constructed dwellings. Staff from NORC at the University of Chicago, The Associated Press, and The SCAN Foundation collaborated on all aspects of the study.

Interviews for this survey were conducted between March 2 and March 29, 2017, with adults age 40 and older representing the 50 states and the District of Columbia. Panel members were randomly drawn from AmeriSpeak, and 1,341 completed the survey—1,106 via the web and 235 via telephone. The sample also included an oversample of Hispanic adults—310 Hispanics age 40 and older. Interviews were conducted in both English and Spanish, depending on respondent preference. Respondents were offered a small monetary incentive ($3) for completing the survey.

The final stage completion rate is 37.2 percent, the weighted household panel response rate is 34.4 percent, and the weighted household panel retention rate is 94.7 percent, for a cumulative response rate of 12.1 percent. The overall margin of sampling error is +/- 4.0 percentage points at the 95 percent confidence level, including the design effect. For the oversample of Hispanics, the margin of sampling error at the 95 percent confidence level is +/- 9.2 percentage points.

Once the sample has been selected and fielded, and all the study data have been collected and made final, a poststratification process is used to adjust for any survey nonresponse as well as any noncoverage or under- and oversampling resulting from the study-specific sample design. Poststratification variables included age, gender, census division, race/ethnicity, and education. Weighting variables were obtained from the 2016 Current Population Survey. The weighted data reflect the U.S. population of adults age 18 and over.

In 2013-2016, interviews were conducted through a random digit dial telephone survey on landlines and cell phones with samples of adults age 40 and older. The trend findings should be considered keeping in mind the mode change from the telephone surveys in prior years of the poll to the mixed web and telephone method using the AmeriSpeak Panel for the 2017 poll.

All analyses were conducted using STATA (version 14), which allows for adjustment of standard errors for complex sample designs. All differences reported between subgroups of the U.S. population are at the 95 percent level of statistical significance, meaning that there is only a 5 percent (or less) probability that the observed differences could be attributed to chance variation in sampling. Additionally, bivariate differences between subgroups are only reported when they also remain robust in a multivariate model controlling for other demographic, political, and socioeconomic covariates.

A comprehensive listing of all study questions, complete with tabulations of top-level results for each question, is available on The AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research long-term care website: www.longtermcarepoll.org.

Contributing Researchers

From NORC at the University of Chicago

Jennifer Benz

Jennifer Titus

Dan Malato

Liz Kantor

Trevor Tompson

From The Associated Press

Emily Swanson

About The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research

The AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research taps into the power of social science research and the highest-quality journalism to bring key information to people across the nation and throughout the world.

- The Associated Press (AP) is the world’s essential news organization, bringing fast, unbiased news to all media platforms and formats.

- NORC at the University of Chicago is one of the oldest and most respected, independent research institutions in the world.

The two organizations have established The AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research to conduct, analyze, and distribute social science research in the public interest on newsworthy topics, and to use the power of journalism to tell the stories that research reveals.

The founding principles of The AP-NORC Center include a mandate to carefully preserve and protect the scientific integrity and objectivity of NORC and the journalistic independence of AP. All work conducted by the Center conforms to the highest levels of scientific integrity to prevent any real or perceived bias in the research. All of the work of the Center is subject to review by its advisory committee to help ensure it meets these standards. The Center will publicize the results of all studies and make all datasets and study documentation available to scholars and the public.

Footnotesꜛ

1. Administration on Aging, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2015. A Profile of Older Americans: 2015. https://www.acl.gov/sites/default/files/Aging%20and%20Disability%20in%20America/2015-Profile.pdfꜛ

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Clearinghouse for Long-Term Care Information. 2015. The Basics. http://longtermcare.gov/the-basics/ꜛ

3. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2015. Long-Term Services and Supports for Older Americans: Risks and Financing Research Brief. https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/long-term-services-and-supports-older-americans-risks-and-financing-research-briefꜛ

4. https://www.caring.com/articles/medicare-home-careꜛ

5. In 2013-2016, interviews were conducted through a random digit dial telephone survey on landlines and cell phones with samples of adults age 40 and older. In 2017, interviews were conducted via either web or phone using the AmeriSpeak Panel, the probability-based panel of NORC at the University of Chicago. Reports and topline findings for all years can be found at https://longtermcarepoll.org/Pages/Default.aspx.ꜛ

6. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Clearinghouse for Long Term Care Information. 2015. Who Needs Care? https://longtermcare.acl.gov/the-basics/who-needs-care.htmlꜛ

7. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2015. Long-Term Services and Supports for Older Americans: Risks and Financing Research Brief. https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/long-term-services-and-supports-older-americans-risks-and-financing-research-briefꜛ

8. Survey respondents were informed that the population of older adults is expected to nearly double by the year 2040. Administration on Aging, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2014. A Profile of Older Americans: 2014. https://www.acl.gov/sites/default/files/Aging%20and%20Disability%20in%20America/2014-Profile.pdf ꜛ

9. This group includes those who are currently receiving or providing ongoing living assistance, have received or provided assistance in the past, and those who say they or anyone in their family is currently employing someone to provide in-home ongoing living assistance.ꜛ

10. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Clearinghouse for Long Term Care Information. 2015. Who Needs Care? https://longtermcare.acl.gov/the-basics/who-needs-care.htmlꜛ

11. http://www.longtermscorecard.org/2014-scorecardꜛ

12. Genworth Financial. April 2016. Genworth 2016 Cost of Care Survey. https://www.genworth.com/about-us/industry-expertise/cost-of-care.htmlꜛ

13. American Elder Care Research Organization. June 2016. Paying for Senior Care. https://www.payingforseniorcare.com/longtermcare/paying-for-nursing-homes.htmlꜛ

14. https://www.caring.com/articles/medicare-home-careꜛ

15. https://www.ssa.gov/news/press/factsheets/basicfact-alt.pdfꜛ

16. http://www.thescanfoundation.org/sites/default/files/who_pays_for_ltc_us_jan_2013_fs.pdfꜛ

17. http://www.nationalpartnership.org/research-library/work-family/paid-leave/state-paid-family-leave-laws.pdfꜛ

18. Hillary for America. 2016. Paid Family and Medical Leave: It’s Time to Guarantee Paid Family and Medical Leave in America. https://www.hillaryclinton.com/issues/paid-leave/ꜛ

19. Bernie 2016. 2016. Issues: Real Family Values. https://berniesanders.com/issues/real-family-values/ꜛ

20. http://www.king.senate.gov/download/?id=47B89267-C4AA-4C33-889B-995761622661&inline=fileꜛ

21. http://www.gillibrand.senate.gov/issues/paid-family-medical-leaveꜛ

22. Hillary for America. 2016. Hillary Clinton’s Plan to Invest in the Caring Economy: Recognizing the Value of Family Caregivers and Home Care Workers. https://www.hillaryclinton.com/briefing/factsheets/2015/11/22/caring-economy/ꜛ

23. https://www.usnews.com/news/us/articles/2015/09/25/rubio-proposes-employer-tax-credit-for-paid-family-leaveꜛ