In this photo taken Wednesday, Jan. 19, 2011, senior citizens do physical therapy at the Glendale Gardens Adult Day Health Care center in Glendale, Calif. Senior health care benefits could come to an end if proposed budget cuts are carried out to help reverse California's $28 billion deficit (AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes)

The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research, with funding from The SCAN Foundation, is undertaking a series of major studies on the public’s experiences with, and opinions and attitudes about, long-term care in the United States. An objective of the 2014 study was to dig deeper into the experiences and opinions about long-term care among Californians age 40 or older. According to the California Department of Finance, adults age 65 and older will comprise about 19 percent of the state’s population by 2030. At the same time, the state’s senior population is growing more diverse—by 2020, white residents will make up 55 percent of those age 65 and older, Hispanics will make up 22 percent, Asians 15 percent and blacks 5 percent. The implementation of policies in the state to address long-term care among certain populations—such as the Coordinated Care Initiative that changes the way long-term care is delivered to low-income seniors and individuals with disabilities—makes tracking opinion in this state important for understanding evolving attitudes on the issue.

California’s diverse aging population, moreover, allows for a closer examination of how a variety of demographic groups—including foreign-born adults, those in multilingual households, and those in multigenerational households—experience long-term care in America.

In order to produce new and actionable data about the aging population to inform the dialogue surrounding long-term care issues, the AP-NORC Center conducted 1,745 interviews with a nationally representative sample of adults age 40 or older. The study also included an oversample of 485 Californians and 458 Hispanics nationwide age 40 or older. Key findings on the California data are presented below:

- Nearly two-thirds of Californians age 40 or older say they will need ongoing living assistance1 someday, yet the majority have done little or no planning for their own ongoing living assistance needs.

- Across demographic groups, a majority say they can rely on their family as they age, with differences based on age and household composition. Compared to the rest of the country, however, fewer Californians say they have discussed their long-term care planning needs with loved ones.

- Similar to the rest of the country, Californians age 40 or older are more likely to have planned for their death than for long-term care—yet there are sharp differences across demographic groups in long-term care planning behaviors.

- Hispanics and those born outside of the United States express greater concern than others about a number of aspects of aging.

- Confidence in one’s ability to pay for long-term care is lower among foreign-born Californians, those who are younger, and women.

- Among California’s caregivers, most acknowledge the stress of providing care to family or close friends, but overall they remain positive about the experience. Differences emerge based on a number of socioeconomic factors.

- While 6 in 10 Californians age 40 or older expect a loved one to need care in the next five years, non-Hispanic whites, U.S.-born Californians, and those in higher-income households are much more likely than others to have planned for their loved one’s care.

- Polarization on some long-term care policies is greater among partisans in California than among partisans in the rest of the country, yet Democrats, Republicans, and independents agree on the extent to which individuals and families should be responsible for care costs relative to the government and insurers.

Additional information, including the survey’s complete topline findings, can be found on the AP-NORC Center’s long-term care project website at www.longtermcarepoll.org.

In California, there are sharp differences across a number of demographic groups in levels of concern about certain aspects of aging.ꜛ

In general, Californians age 40 or older hold similar levels of concern about certain aspects of aging when compared to those in the rest of the country. About half have a great deal or quite a bit of concern with losing their memory or other mental abilities (51 percent) or are concerned with losing their independence (50 percent). Less than half (44 percent) are concerned with being able to pay for any care they might need as they age, 36 percent with being a burden on their family, and 35 percent with having to leave their home and move into a nursing home. A third of Californians 40 or older are concerned with being alone without family or friends and 32 percent with not planning enough for the care they might need as they age. While the national data reveal significant differences in concern about aging between those who have experience providing or receiving care, in California, there is little difference in concern about aging based on experience with caregiving.

Yet, there are stark differences among Californians in levels of concern on a number of aspects of aging depending on socioeconomic factors. For example, non-Hispanic whites (37 percent) are much less concerned than Hispanics (55 percent) with being able to pay for the care they might need as they age. In addition, non-Hispanic whites are also less concerned than Hispanics with being alone without family or friends nearby (27 percent vs. 43 percent). Hispanics living in California are also more concerned than Hispanics in the rest of the country about being alone as they age (43 percent vs. 31 percent).

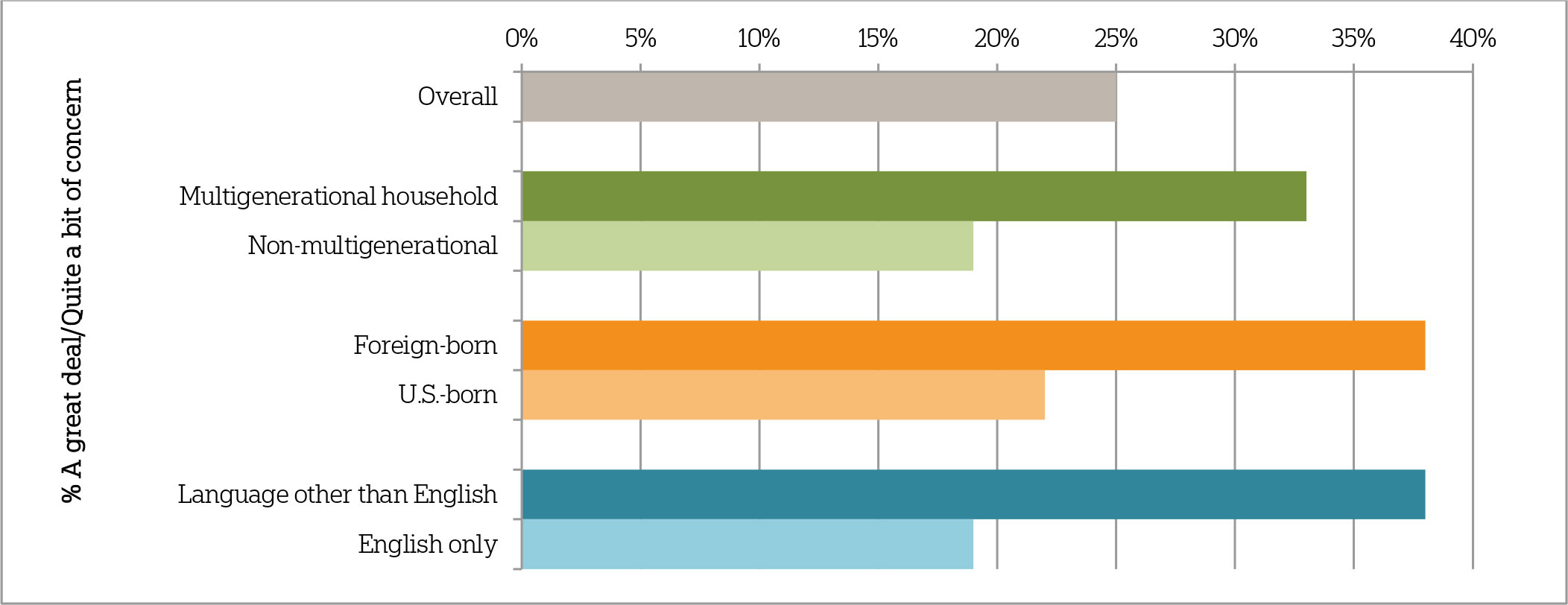

There are also differences in concern between Californians age 40 or older who are foreign-born and U.S.-born, those living in multigenerational households compared to those who are not, and those who only speak English at home compared to those who speak languages other than English. Californians who are foreign-born and those who speak a language other than English at home (38 percent each) are much more likely to express concern about leaving debts to their family than those who were born in the United States (22 percent) and those who speak only English at home (19 percent). A third of Californians living in multigenerational households2—42 percent of those surveyed—are concerned with leaving debts to their family, compared to less than 1 in 5 of those who do not live in such households (19 percent).

Concern with leaving debts to their family as they get older by demographic groups in California

Question: Thinking about your own personal situation as you get older, for each item please tell me if it causes you a great deal of concern, quite a bit of concern, a moderate amount, only a little, or none at all? How about leaving debts to your family?

Foreign-born residents (55 percent) are twice as likely to say they are worried about being alone as they age as U.S.-born residents (27 percent). And those who speak a language other than English at home (47 percent) are much more likely than those who speak only English (26 percent) to express concern about this aspect of aging.

Financial preparedness for long-term care differs sharply across demographic groups within California.ꜛ

Like the rest of the nation, Californians age 40 or older are not very confident they will have the financial resources to pay for care they might need as they age. Just 3 in 10 Californians and adults 40 or older nationwide say they are extremely or very confident about their ability to pay for future care; 36 percent of Californians report that they are somewhat confident, and a third say they are not too or not at all confident.

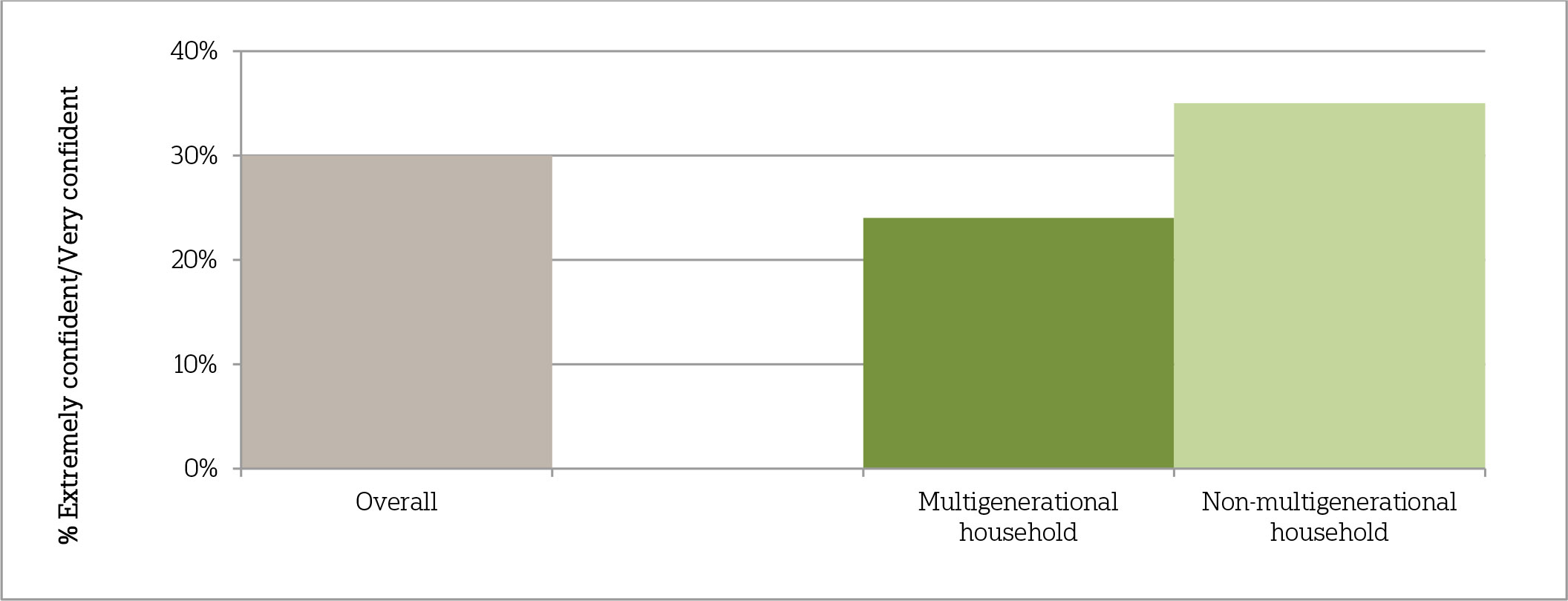

While those with higher income levels are more confident about paying for future care, confidence levels differ across a number of demographic groups—even after controlling for this factor. A majority of foreign-born Californians age 40 or older (58 percent) say they are not too or not at all confident in their ability to pay for their own future care, compared to about a quarter (26 percent) of U.S.-born Californians. Californians between the ages of 40 and 65 are more likely to lack confidence about paying for future care than those who are 65 and older. Women (41 percent) are also more likely than men (25 percent) to say they are not too or not at all confident about their ability to pay for care in the future. Those living in multigenerational households (24 percent) are less likely to say they are confident about paying for future care than those who do not live in such households (35 percent).

Confidence in having the financial resources to pay for long-term care as they age

Question: How confident are you that you will have the financial resources to pay for any care you need as you get older?

When it comes to estimating the actual cost of long-term care in California, most Californians age 40 or older offer incorrect estimates for the cost of a nursing home, an assisted living facility, and an in-home health care aide. Despite the fact that care costs are higher in California, residents of the state who are 40 or older are just as likely as those in the rest of the country to underestimate the average monthly cost to live in a nursing home, with 54 percent saying it costs less than $6,000. Californians also tend to overestimate the costs of living in an assisted living facility, with 38 percent citing monthly costs greater than $4,000. Further, Californians 40 or older overestimate the average monthly cost for part-time care from a home health care aide—49 percent say it costs more than $2,000.3

Those who speak a language other than English at home are more likely than those who speak only English to underestimate the cost of care in nursing homes and assisted living facilities. In addition, Hispanics are less likely than non-Hispanic whites to offer the correct estimates for those types of care. Similar to the national findings, those 40 and older with higher education levels more accurately estimate the cost of these long-term care services.

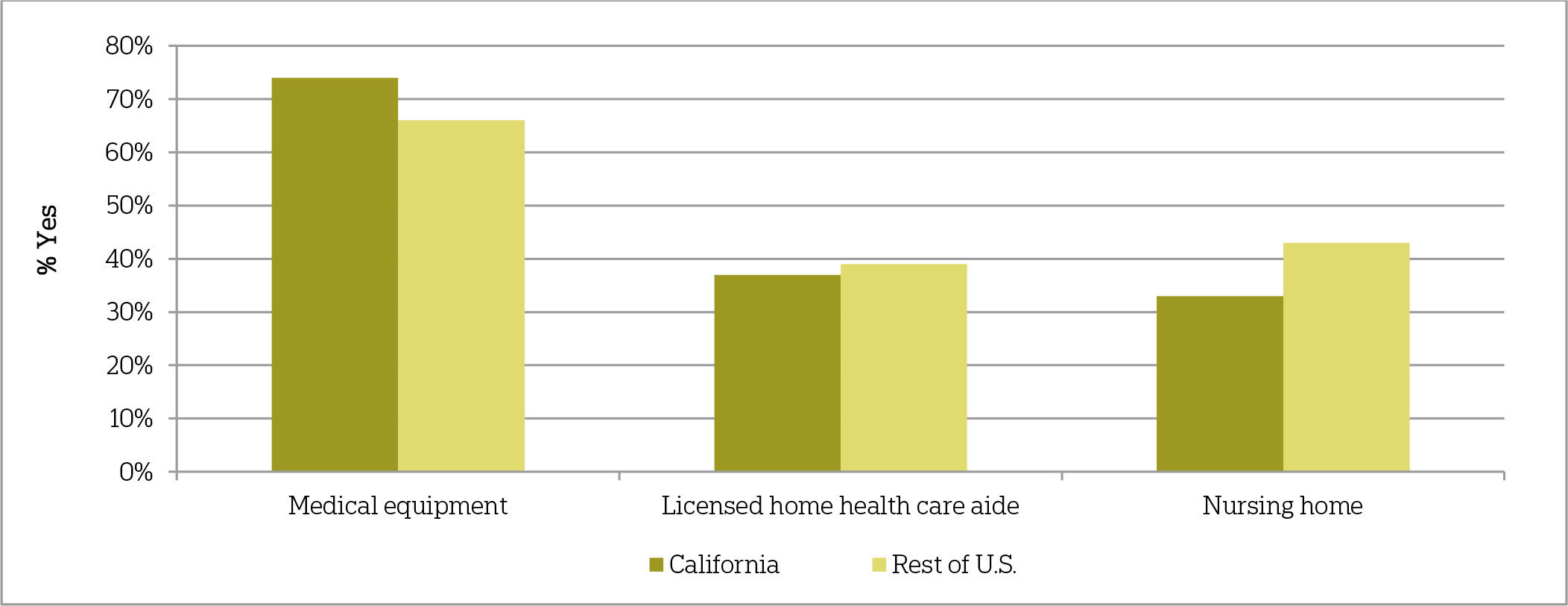

Californians also overestimate the long-term care services that Medicare will cover. Generally, Medicare pays for skilled nursing facility stays in only certain circumstances, and for brief periods of time.4 Compared to adults age 40 or older in the rest of the country, Californians are more likely to be unsure about whether Medicare pays for ongoing care in a nursing home. A third of Californians 40 or older (33 percent) say that Medicare pays for this service, a third say it does not, and 28 percent say they do not know; 43 percent of adults in the rest of the country think Medicare pays for this care, 29 percent think it does not, and 21 percent report that they do not know. Californians age 40 or older (74 percent) are also more likely than those in the rest of the country (66 percent) to say Medicare pays for medical equipment such as wheelchairs and other assistive devices, which is true if a physician prescribes this equipment as medically necessary. Nearly 4 in 10 Californians believe that Medicare pays for ongoing care at a home by a licensed home health care aide.

As far as you know, does Medicare pay for the following or not?

Medicaid, a government health care coverage program for low-income people and people living with certain disabilities, is the single largest payer for long-term care services in the United States.5 Despite a general lack of confidence among Californians age 40 or older in their ability to pay for long-term care services, a majority (52 percent) say they will not need to rely on Medicaid, known as Medi-Cal in California, to pay for such expenses. Those who lack confidence about their financial resources to pay for long-term care are more likely to say they will have to rely on Medicaid. Sixty-two percent of those who are not too or not at all confident about their financial resources say they will have to rely on Medicaid, compared to 34 percent of those who are somewhat confident and 16 percent of those who are extremely or very confident about their resources.

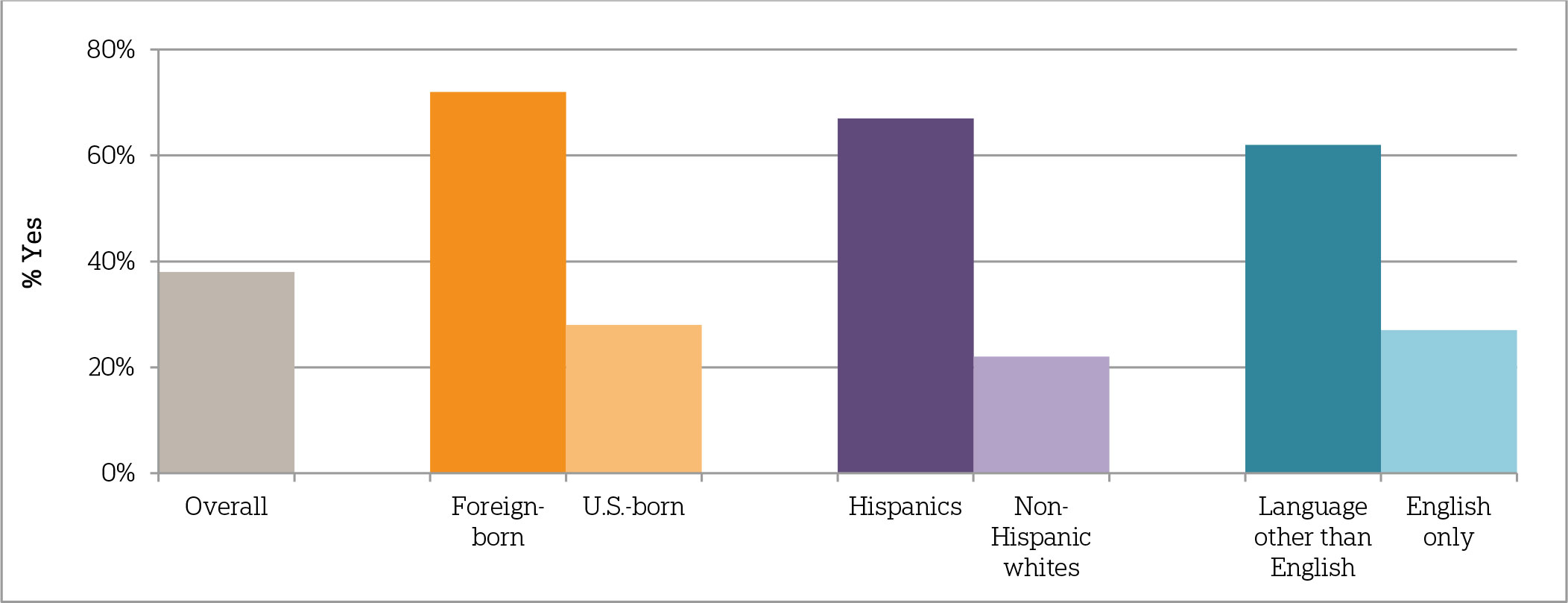

There are stark differences across certain demographic groups in the perception that Medicaid will be necessary, even after controlling for income and various socioeconomic variables. The difference is particularly pronounced between foreign-born and U.S.-born Californians age 40 or older, with 72 percent of those who are foreign-born saying they will need to rely on Medicaid for long-term care expenses, compared to just 28 percent of U.S.-born Californians. Further, two-thirds of Hispanics (67 percent), indicate they will rely on Medicaid, while far fewer non-Hispanic whites (22 percent) say they will need this program. Over 6 in 10 of those living in households where a language other than English is spoken say they will rely on Medicaid for long-term care, in contrast to 27 percent of those living in English-only households.

Percent of Californians age 40 or older who say they will need to rely on Medicaid for long-term care

Question: Medicaid is a government health care coverage program for low-income people and people with certain disabilities. Do you think you will need Medicaid to help pay for your ongoing living assistance expenses as you grow older or not?

Californians in multigenerational households are much more confident in their ability to rely on family as a support system.ꜛ

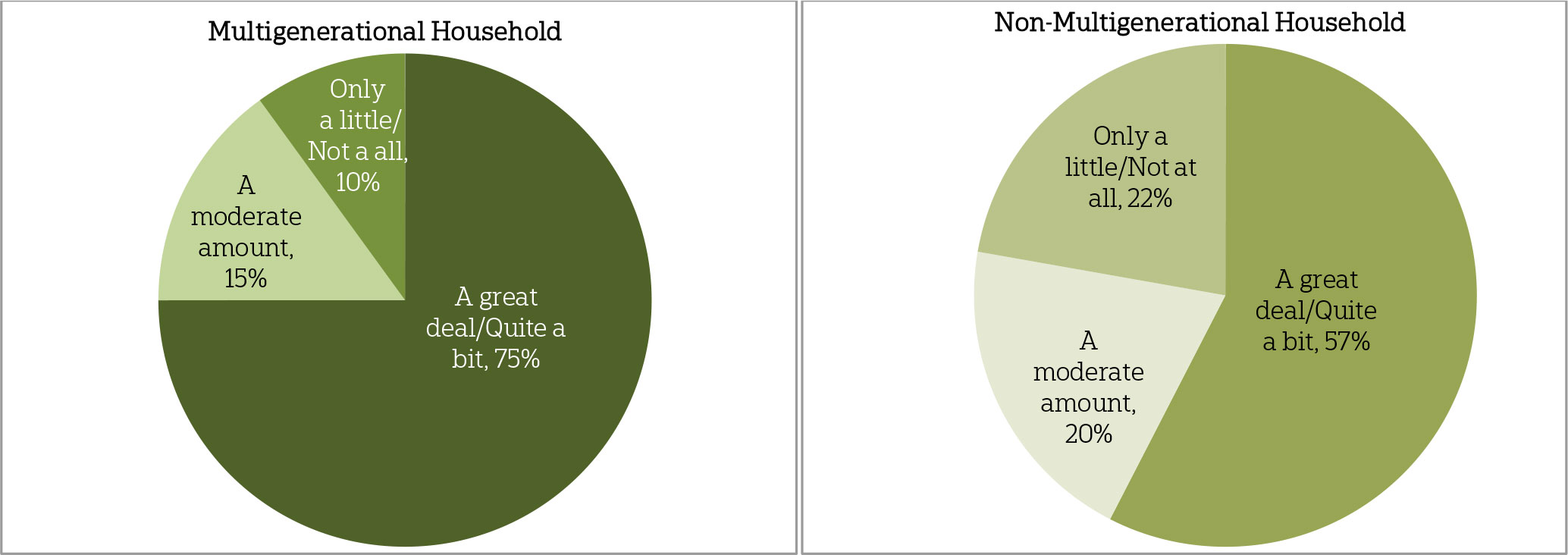

Over 6 in 10 Californians age 40 or older (64 percent) say they can rely on their family either a great deal (49 percent) or quite a bit (15 percent) to be there for them in a time of need. Seventeen percent say they can rely on their family only a little or not at all. Majorities across demographic groups think they can rely on their family, yet there are differences based on age and household composition. Californians who report living in multigenerational households are much more likely than those who do not to say they can rely on family (75 percent vs. 57 percent). Seventy-three percent of Californians age 65 or older think they can rely on their family, compared to 58 percent of those age 55–64; 63 percent of those age 40–54 say they can rely on their family when in need.

Perceptions about being able to rely on family by household composition

Question: How much do you feel you can rely on your family to be there for you in a time of need?

Similar to adults in the rest of the United States, Californians are most likely to think that their spouses will provide them with help as they age, compared to other family members. Over 7 in 10 Californians who have a spouse or partner (72 percent) think their significant other will provide them with a great deal or quite a bit of help. Four in 10 Californians age 40 or older who are parents think they will be able to rely on their children or grandchildren as they age, and 27 percent say they will be able to rely on their extended family members.

Despite being more likely to say they can rely on their family generally, when asked about the help they can expect from spouses, children and grandchildren, and extended family specifically, Californians in multigenerational households are just as likely as those who are not living in multigenerational households to say these family members will help them as they age.

Compared to adults age 40 or older in the rest of the United States, Californians are less sure about help from extended family members—nearly half say they expect only a little or no help at all from extended family, compared to 41 percent of those living outside of California. And while the national study found that women are much more likely to say they could rely on their children, grandchildren, and extended family members as they age, women in California are just as likely as men to say these support systems will provide them help.

When it comes to institutional support systems, 42 percent of Californians age 40 or older think doctors, nurses, and other health care providers will provide them with a great deal or quite a bit of help as they age. Thirty-six percent think the health insurance system or Medicare will provide help, and 17 percent say they can expect to rely on Medicaid. Californians 40 or older who live in households earning less than $50,000 per year (35 percent) are less likely than those earning more (46 percent) to say they will get help from doctors, nurses, and other health care providers, but more likely to say they will get help from the Medicaid system (23 percent vs. 12 percent, respectively). Men in California are more likely than women to say they can rely on the health insurance system (42 percent vs. 30 percent) and doctors, nurses, and other health care providers (49 percent vs. 35 percent).

Californians overall are positive about their caregiving experiences, though these experiences vary depending on socioeconomic circumstances.ꜛ

Similar to the rest of the United States, 57 percent of Californians age 40 or older have experience with ongoing living assistance, either receiving it (10 percent), providing care directly (52 percent), or they or someone in their family is paying for care (7 percent). Over 6 in 10 care recipients (62 percent) are women, with an average age of 63 years old. A majority of care providers (57 percent) are also women, about half (48 percent) have household incomes of less than $50,000 per year, and their average age is 60 years old. Half of Hispanics (50 percent) and a majority of non-Hispanic whites (55 percent) are or have been care providers, as are 45 percent of those who speak a language other than English at home, 52 percent of those living in multigenerational households, 54 percent of U.S.-born, and 46 percent of foreign-born Californians.

Californians age 40 or older who are currently or have ever provided care are most likely to have provided care to family members, including their mothers (42 percent), followed by their fathers (16 percent), spouses or partners (15 percent), parents-in-law (8 percent), children (8 percent), grandparents (7 percent), and extended family members (7 percent). Californians who are care providers are about two times more likely than those in the rest of the United States to say they have provided care to a close friend (13 percent vs. 6 percent).

In general, Californians age 40 or older who have provided care to a loved one reveal positive sentiments about the experience. Nearly 8 in 10 (79 percent) say it was a positive experience in their life, and 77 percent say it has strengthened their personal relationship with the person for whom they provided care, while just 9 percent say it has weakened that relationship. Still, a majority (57 percent) say it has caused stress in their family, 43 percent that it has taken time away from family life, 34 percent say it has taken time away from work, and 31 percent that it has been a burden on personal finances.

Californians age 40 or older living in multigenerational households are less likely than those not living in multigenerational households to say caregiving has taken time away from family (33 percent vs. 49 percent). And those in higher-income households (64 percent) are more likely than those with lower incomes (47 percent) to say it caused stress in the family. Despite higher costs for long-term care in California, those in higher- and lower-income households are equally as likely to say providing care was a burden on their finances (29 percent each).

Majorities of Californians across demographic groups say it’s likely they will provide care to a loved one in the next five years, but some groups are more likely to be planning for that care.ꜛ

About 6 in 10 Californians age 40 or older (61 percent) think it is at least somewhat likely that an aging family member or close friend will need ongoing living assistance in the next five years, with nearly a third (31 percent) saying it is extremely likely. Three in 10 who foresee a loved one’s need for care in the next five years think that they, personally, will be responsible for providing that ongoing living assistance, 58 percent say someone else will be responsible, and 9 percent say it will be a combination of the two.

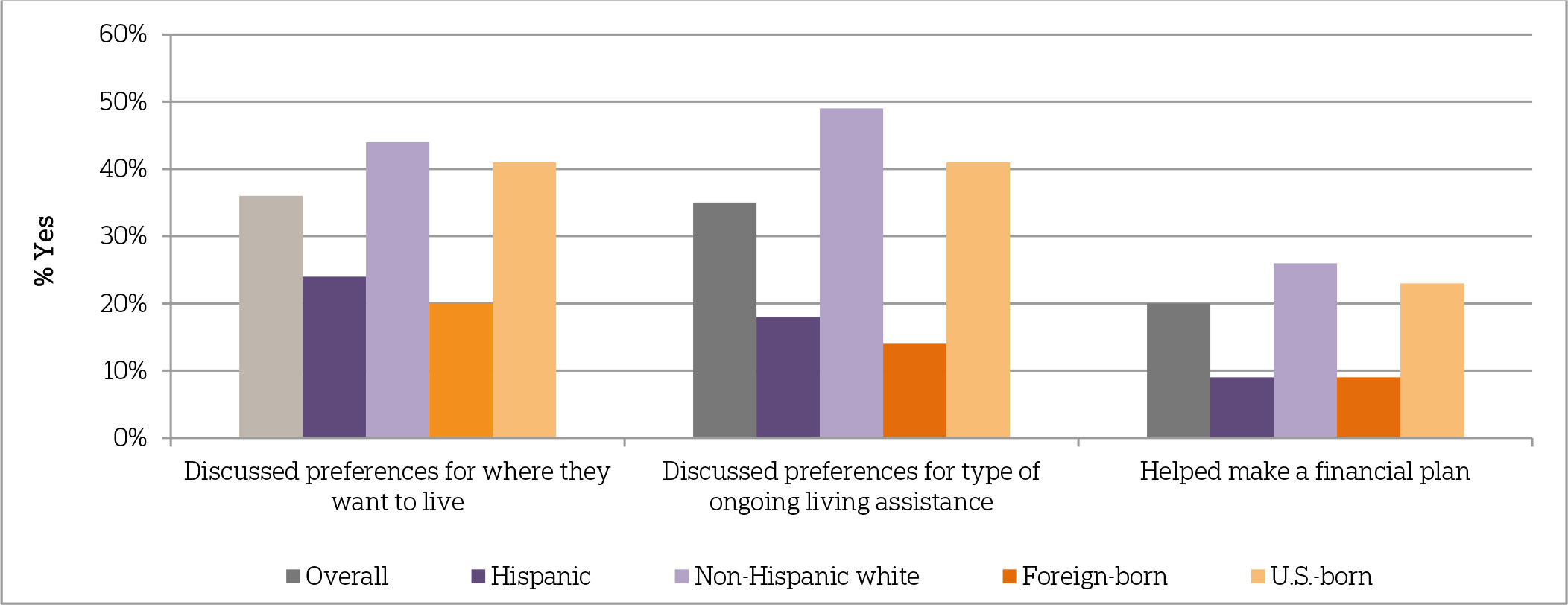

Although expectations about caregiving for a loved one are similar across many demographic groups, some groups are much more likely than others to have actually taken a planning action for a loved one. Overall, only 36 percent have discussed their family member’s preferences for where they want to live while receiving ongoing living assistance, 35 percent have discussed preferences for the kinds of ongoing living assistance they do or do not want, and 20 percent have helped their loved one make a financial plan to pay for ongoing living assistance expenses.

Those who are more confident about having the financial resources to pay for long-term care are more likely to say they have done any of this planning with their loved ones. For example, nearly 3 in 10 who are extremely or very confident about having the financial resources to pay for long-term care have helped their family member make a financial plan, compared to about 1 in 10 who are not too or not at all confident about finances. And just over 4 in 10 who are confident with their long-term care finances have talked with their loved ones about their ongoing living assistance preferences, compared to slightly fewer than 3 in 10 who have little to no confidence.

Further, while nearly half of non-Hispanic whites (47 percent) have discussed preferences with a loved one for the type of ongoing living assistance they would want, fewer than 1 in 5 Hispanics (18 percent) have done so. And while 4 in 10 U.S.-born Californians (41 percent) have discussed these preferences, just 14 percent of foreign-born Californians have had this discussion with a loved one.

Actions taken to plan for a family member’s or friend’s needs across demographic groups

Question: Have you taken any of the following actions to plan for you family member’s or friend’s needs?

Californians are slightly less likely than adults in the rest of the United States to have discussed their long-term care preferences with their family.ꜛ

Although Californians anticipate needing long-term care themselves at about the same rate as those in the rest of the country, Californians are slightly less likely to say they have discussed their own care preferences with loved ones. Sixty-five percent of Californians and 62 percent of adults age 40 or older living outside of California say it is at least somewhat likely they will personally need ongoing living assistance someday. Yet two-thirds of Californians 40 or older report that they have done only a little or no planning at all for their own ongoing living assistance needs; just 13 percent have done a great deal or quite a bit of planning. Those who are older, have higher incomes, or are employed are more likely than others to say they have planned for their own long-term care needs.

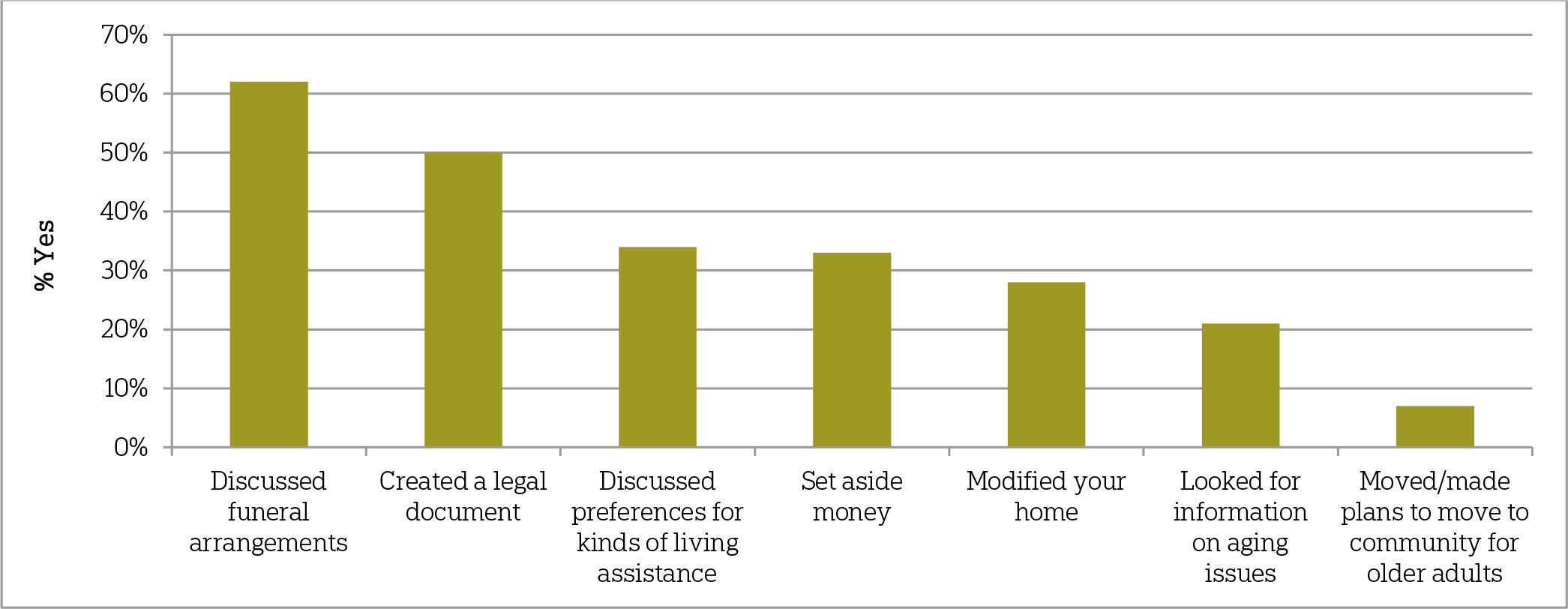

On most planning actions tested in the survey, Californians age 40 or older are about equally as likely as those in the rest of the United States to have completed them. Californians, like Americans generally, are more likely to plan for one’s death rather than for the living assistance one might need as they age. Sixty-two percent have discussed preferences for their funeral with someone they trust, and half have created a legal document such as a living will or advanced directive. Far fewer have set aside money to pay for ongoing living assistance expenses (33 percent), modified their homes to make it easier to live as they grow older (28 percent), looked for information about aging issues and ongoing living assistance (21 percent), or made plans to move to a community or facility designed for older adults (7 percent).

Whatever level of planning they’ve done, though, Californians age 40 or older (65 percent) are more likely than those in the rest of the country (58 percent) to say they have not yet discussed their preferences with family.

Proportion of Californians who have taken long-term care planning actions as they age.

Question: What actions have you taken to plan for your own needs as you age?

Californians think a number of measures would improve the quality of long-term care services.ꜛ

Given a lack of planning for one’s own care needs and a broad misunderstanding of what care costs, Californians generally agree that a number of measures would help improve the quality of ongoing living assistance for those in need of care. Eight in 10 Californians age 40 or older (81 percent) think it would be extremely or very helpful to provide access to services in the community that help people continue to live independently. Nearly 8 in 10 say ensuring that all care is focused on the person’s quality as well as length of life—and providing affordable care programs that give the family caregiver the opportunity to take breaks from caregiving—would be helpful. Seven in 10 say letting a family member take time away from work would help, two-thirds think taking into account an individual’s personal goals and preferences would help, and 6 in 10 say designating a caregiver on the medical chart and including them in all discussions about care would help. Those with and without care experience—either as a caregiver or provider—agree in similar proportions that each of these actions would improve the quality of long-term care.

People across a number of demographic and socioeconomic groups agree that these measures would help improve long-term care. However, even controlling for these demographic and socioeconomic factors, there are differences in the degree to which these actions are considered helpful based on partisanship. Democrats are more likely than Republicans to think designating a single case manager, designating a caregiver on a medical chart, providing affordable care programs, and providing access to community services would help improve the quality of long-term care.

A majority of Californians support several policies to help Americans pay for long-term care, though the degree of polarization between partisans on some issues is greater in California than in the rest of the nation. ꜛ

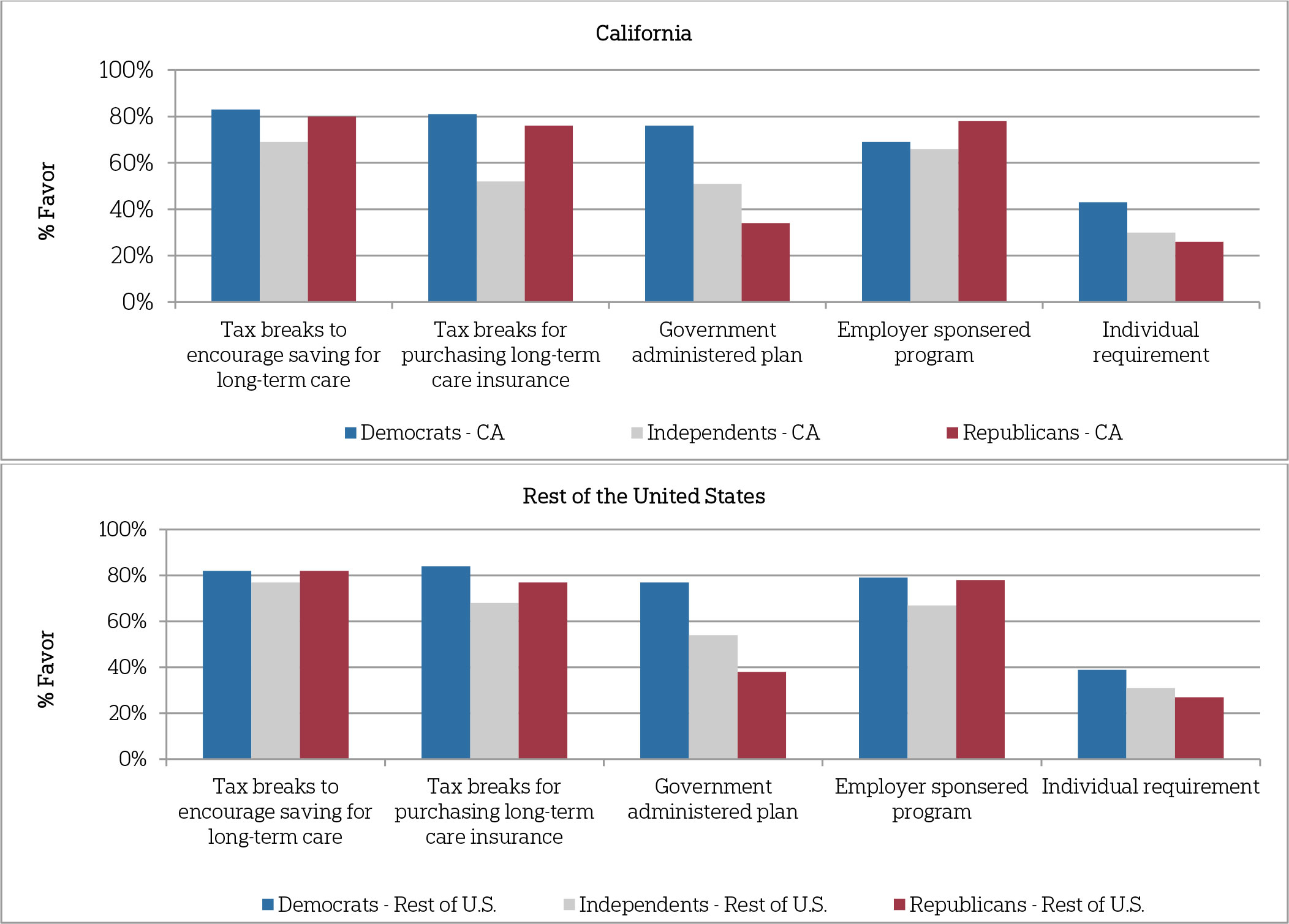

The survey tested support for five distinct policy measures that might help Americans prepare for the cost of ongoing living assistance. Similar to adults age 40 or older in the rest of the United States, Californians are most likely to favor tax breaks to encourage saving for ongoing living assistance expenses (79 percent), tax breaks for consumers who purchase long-term care insurance (73 percent), and the ability for individuals to purchase long-term care insurance through their employers (71 percent). Majorities across demographic groups favor each of these long-term care policies. A smaller majority (59 percent) favor a government administered long-term care insurance program, similar to Medicare. Just 36 percent favor a requirement that individuals purchase long-term care insurance, though Californians are slightly more likely than adults in the rest of the country to say they strongly favor this idea (20 percent vs. 15 percent, respectively).

The partisan divide in California on some of these policies is consistent with findings among adults age 40 or older in the rest of the country, with Democrats more likely to support a government administered plan and an individual requirement. Yet, there is more polarization in California on some issues. For example, Democrats’ support for an individual requirement is 17 percentage points greater than Republicans in California, compared to a 12 percentage point difference in the rest of the United States. Further, while Democrats and Republicans at both the national level and in California tend to agree on tax breaks for consumers and for long-term care savings, independents—albeit still a majority—are less likely to support these policies. And in California, independents are much less likely to support tax breaks for purchasing long-term care insurance than independents in the rest of the country (52 percent vs. 68 percent). Finally, Californians who are foreign-born are more likely than U.S.-born Californians age 40 or older to support a government administered long-term care plan (73 percent vs. 55 percent).

Support for long-term care policies by political party affiliation in California and the rest of the United States.

Question: To help Americans prepare for the costs of ongoing living assistance, sometimes referred to as long-term care, would you favor, oppose, or neither favor nor oppose (ITEM)?

In contrast to partisans in the rest of the United States, Democrats, Republicans, and independents in California hold similar views on the level of responsibility individuals and families should assume for long-term care.ꜛ

Asked who should be responsible for paying for the costs of ongoing living assistance, the largest share of Californians (49 percent) say insurance companies should have a very large or large responsibility, despite the fact that many insurance plans do not cover long-term care expenses. Forty-two percent say individuals should be responsible, 39 percent say Medicare should be responsible, 36 percent say Medicaid should be responsible, and the fewest—22 percent—say families should be responsible. These results mirror those among adults age 40 or older in the rest of the country.

While outside of California there are clear differences in opinion among Democrats and Republicans on who should pay for ongoing living assistance, in California Democrats and Republicans hold similar views. In the rest of the United States, Republicans (53 percent) are far more likely than Democrats (31 percent) and independents (36 percent) to say individuals should be responsible. Yet in California, 4 in 10 across parties think individuals should be responsible. Experience with care does not affect one’s opinion about an individual’s level of responsibility.

Among Californians, similar proportions of Democrats (22 percent) and Republicans (24 percent) think families should be responsible for covering the costs of care, though Republicans are twice as likely as Democrats to think that role should be very large (14 percent to 7 percent). Among partisans in the rest of the United States, Republicans (28 percent) are much more likely than Democrats (13 percent) to say that families should hold a very large or large level of responsibility.

Similar to partisans in the rest of the country, partisans in California differ in the degree to which they think institutional actors should play a role. Reflecting the more polarized nature of partisans in California on some of the policy questions mentioned above, Democrats and Republicans are even more divided on the question of how insurance companies and Medicaid should be involved than are partisans in the rest of the country. A majority (56 percent) of Democrats in California think insurance companies should play a large or very large role, compared to 40 percent of Republicans. Forty-three percent of Democrats think Medicaid should play a role, compared to a quarter (24 percent) of Republicans.

About the Studyꜛ

Study Methodology

This survey, funded by The SCAN Foundation, was conducted by the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research between the dates of March 13 through April 23, 2014. Staff from NORC at the University of Chicago, the Associated Press, and The SCAN Foundation collaborated on all aspects of the study.

This random-digit-dial (RDD) survey of the 50 states and the District of Columbia was conducted via telephone with 1,745 adults age 40 or older. In households with more than one adult age 40 or older, we used a process that randomly selected which eligible adult would be interviewed. The sample included 1,340 respondents on landlines and 405 respondents on cell phones. The sample also included oversamples of Californians and Hispanics nationwide age 40 or older. The sample includes 485 residents of California age 40 or older and 458 Hispanics from the 50 states and the District of Columbia age 40 or older. Cell phone respondents were offered a small monetary incentive for participating, as compensation for telephone usage charges. Interviews were conducted in both English and Spanish, depending on respondent preference. All interviews were completed by professional interviewers who were carefully trained on the specific survey for this study.

The RDD sample was provided by a third-party vendor, Marketing Systems Group. The final response rate was 22 percent, based on the American Association of Public Opinion Research Response Rate 3 method.

Sampling weights were calculated to adjust for sample design aspects (such as unequal probabilities of selection) and for nonresponse bias arising from differential response rates across various demographic groups. Poststratification variables included age, sex, race, region, education, and landline/cell phone use. The weighted data, which thus reflect the U.S. population, were used for all analyses. The overall margin of error for the national sample is +/- 3.6 percentage points, including the design effect resulting from the complex sample design. The overall margin of error for the California sample is +/-5.3 percentage points, and the overall margin of error for the Hispanic sample is +/-6.8 percentage points.

All analyses were conducted using STATA (version 13), which allows for adjustment of standard errors for complex sample designs. All differences reported between subgroups of the U.S. population are at the 95 percent level of statistical significance, meaning that there is only a 5 percent (or less) probability that the observed differences could be attributed to chance variation in sampling. Additionally, bivariate differences between subgroups are only reported when they also remain robust in a multivariate model controlling for other demographic, political, and socioeconomic covariates. A comprehensive listing of all study questions, complete with tabulations of top-level results for each question, is available on the AP-NORC Center’s long-term care website: www.longtermcarepoll.org.

Contributing Researchers

From NORC at the University of Chicago

Jennifer Benz

Nicole Willcoxon

Emily Alvarez

Dan Malato

Trevor Tompson

From The Associated Press

Jennifer Agiesta

Dennis Junius

About the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research

The AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research taps into the power of social science research and the highest-quality journalism to bring key information to people across the nation and throughout the world.

- The Associated Press (AP) is the world’s essential news organization, bringing fast, unbiased news to all media platforms and formats.

- NORC at the University of Chicago is one of the oldest and most respected, independent research institutions in the world.

The two organizations have established The AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research to conduct, analyze, and distribute social science research in the public interest on newsworthy topics, and to use the power of journalism to tell the stories that research reveals.

The founding principles of the AP-NORC Center include a mandate to carefully preserve and protect the scientific integrity and objectivity of NORC and the journalistic independence of AP. All work conducted by the Center conforms to the highest levels of scientific integrity to prevent any real or perceived bias in the research. All of the work of the Center is subject to review by its advisory committee to help ensure it meets these standards. The Center will publicize the results of all studies and make all datasets and study documentation available to scholars and the public.

The complete topline data and an analysis of the national findings are available at www.longtermcarepoll.org.

Footnotesꜛ

1. Ongoing living assistance was defined for respondents as “assistance can be help with things like keeping house, cooking, bathing, getting dressed, getting around, paying bills, remembering to take medicine, or just having someone check in to see that everything is okay. This help can happen at your own home, in a family member’s home, in a nursing home, or in a senior community. And, it can be provided by a family member, a friend, a volunteer, or a health care professional.”ꜛ

2. This variable was created based on the following question: “Thinking about all the people you live with in your household, please tell me how they are related to you?” Response options included spouse/partner, children, grandchildren, parent(s) or in-laws(s), grandparents, siblings, other relatives, other non-relatives, or live alone. Multigenerational household respondents are defined as those who answered yes that they live with a relative in another generation.ꜛ

3. Costs were determined based on John Hancock’s Cost of Care Study, conducted by LifePlans, Inc., 2013. The California average monthly base rate in an assisted living facility was $3,357 in 2013. The California average hourly rate for home health aides was $21. Part-time was calculated at 2 hours per day for a 30-day month at $21 per hour = $1,260 per month. The California daily average of a semi-private nursing home room is $234. Monthly cost was calculated at $234 for 365 days divided by 12 months.ꜛ

4. Genworth 2013 Cost of Care Survey. Home Care Providers, Adult Day Health Care Facilities, Assisted Living Facilities and Nursing Homes. https://www.genworth.com/dam/Americas/US/PDFs/Consumer/corporate/130568_032213_Cost%20of%20Care_Final_nonsecure.pdf. Accessed May 14, 2014.ꜛ

5. United States Department of Health and Human Services. Who Pays for Long-term Care? http://longtermcare.gov/the-basics/who-pays-for-long-term-care/. Accessed May 14, 2014.ꜛ